Case: Fat Necrosis of the Breast

by Dan Li, MD and Olivia Linden MD

Introduction:

Fat necrosis of the breast is a common benign condition that poses a diagnostic challenge for radiologists. It can mimic malignancy on imaging, leading to unnecessary interventions and patient anxiety.

Epidemiology:

Fat necrosis predominantly affects middle-aged and older women, with a peak incidence in the fifth decade of life.1 It is most often associated with trauma, surgical procedures, and radiation therapy. In rare cases, fat necrosis of the breast can be associated with systemic panniculitides or vasculitis.

Clinical presentation:

Fat necrosis of the breast can be present incidentally or symptomatically, such as with a palpable lump. While often associated with trauma, the traumatic event may not be recalled by the patient and even minor traumas can result in radiographically evident fat necroses.

The imaging appearance of fat necrosis is heterogenous and can vary between different patients and the age of the necrotic foci. An accurate clinical history is essential to confidently diagnose fat necrosis given the heterogeneity of the imaging appearance, but a high index of suspicion must be maintained even in the absence of recalled injury.

Pathophysiology:

Fat necrosis arises from the disruption of adipose tissue integrity, leading to the release of free fatty acids. Trauma, ischemia, and inflammatory processes can initiate this cascade. The necrotic fat then undergoes a series of changes, including liquefaction and encapsulation. Fibrosis can develop around the area of liquefied fat and can either surround or replace the area of necrotic adipose tissue. Eventually, the rim and internal contents of the fat necrosis may calcify, resulting in characteristic benign imaging findings.2

Imaging Findings:

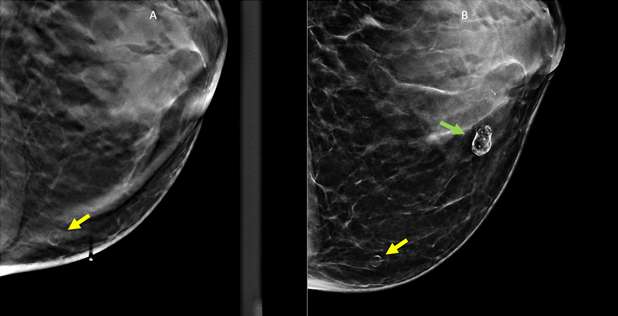

Mammographic Findings: On mammography, fat necrosis typically presents as a well-defined, round or oval mass with varying densities. Initially, it may appear as a radiolucent mass due to the liquefaction of necrotic fat. Chronic lesions may develop rim or “eggshell” calcifications; this appearance is benign when associated with history of trauma and does not require specific imaging follow-up or treatment. As fat necrosis evolves, fibrosis may develop in a spiculated or irregular morphology, which can present similarly on mammogram to breast carcinoma.3 In these cases, correlation with clinical history, close follow-up and/or biopsy may be necessary to distinguish benign fat necrosis from malignant breast masses.

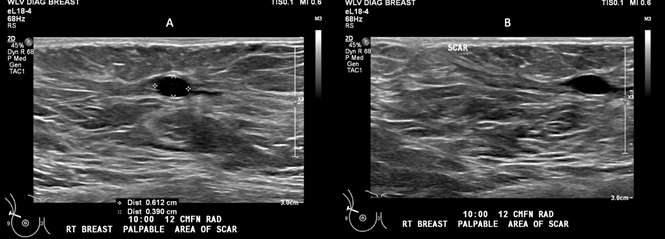

Ultrasound Findings: As with mammography, the ultrasound appearance of fat necrosis is variable and tends to evolve over time. Fat necrosis may appear as a solid, complex cystic and solid, or a cystic/anechoic mass. Complex cystic and solid masses may contain internal echogenicity or mural nodules. Though not always visualized, the presence of shifting positional echogenic bands is relatively specific for fat necrosis.4 When presenting as an anechoic mass/oil cyst, often no posterior acoustic enhancement is present, differing from what would be typical in simple cysts. When intralesional or rim calcifications are present, fat necrosis can be associated with posterior acoustic shadowing, though again the imaging appearance is variable and fat necrosis with posterior acoustic enhancement has also been demonstrated.5

MRI Findings: MRI can be useful when evaluating indeterminate mammographic or ultrasound findings.

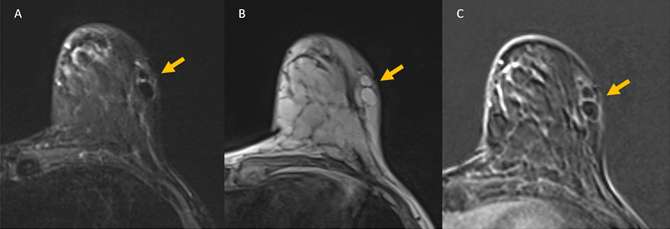

Fat necrosis will follow the signal of fat on all MRI sequences. On T1-weighted images, fat necrosis can present as a heterogeneous mass, with areas of intrinisically bright T1 signal centrally. On fat saturation sequences, fat necrosis will lose signal similar to adjacent fatty breast tissue. On STIR sequences, the area of necrotic fat takes on a characteristic “black hole” appearance with greater signal suppression than normal breast fat.6

In the acute phase, avid peripheral or internal enhancement may be seen, corresponding with areas of developing granulation tissue. The degree of enhancement may decrease over time, as fibrosis develops surrounding the area of injury.7 Enhancement kinetics are variable, with persistent enhancement (type I) being the most common, though plateau and washout kinetics may also be seen (type II and type III).

Management:

True fat necrosis is a benign, self-limited process. When fat necrosis can be confidently diagnosed with imaging, no additional biopsy or surgical evaluation is required, except for patient discomfort or cosmetic concerns.8 In cases where fat necrosis cannot be confidently established based on initial diagnostic imaging, a combination of short-term follow-up, biopsy, or breast surgical consultation may be recommended, depending on the level of suspicion and patient risk factors or preference.

Conclusion:

Fat necrosis of the breast is a benign condition that can mimic malignancy on imaging, necessitating accurate diagnosis to avoid unnecessary interventions. Understanding the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and characteristic imaging findings of fat necrosis is essential for radiologists. Mammography, ultrasound, and MRI play complementary roles in the evaluation of this condition. Familiarity with the diverse imaging features of fat necrosis will aid radiologists in confidently distinguishing it from malignant breast lesions, thereby improving patient management and reducing unnecessary diagnostic procedures.

Figures

References

- Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, Opaluwa AS, Ravikumar KH, Chetty N, Kaplan V, Kelley CJ, Babu ED. "Fat Necrosis of the Breast — A Review." Breast. 2006 Jun;15(3):313-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.003. Epub 2005 Sep 29.

- Kerridge WD, Kryvenko ON, Thompson A, Shah BA. "Fat Necrosis of the Breast: A Pictorial Review of the Mammographic, Ultrasound, CT, and MRI Findings with Histopathologic Correlation." Radiol Res Pract. 2015;2015:613139. DOI: 10.1155/2015/613139. Epub 2015 Mar 16.

- Hogge JP, Robinson RE, Magnant CM, Zuurbier RA. "The Mammographic Spectrum of Fat Necrosis of the Breast." Radiographics. 1995 Nov;15(6):1347-56. DOI: 10.1148/radiographics.15.6.8577961.

- Taboada JL, Stephens TW, Krishnamurthy S, Brandt KR, Whitman GJ. "The Many Faces of Fat Necrosis in the Breast." AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009 Mar;192(3):815-25. DOI: 10.2214/AJR.08.1250.

- Soo MS, Kornguth PJ, Hertzberg BS. "Fat Necrosis in the Breast: Sonographic Features." Radiology. 1998 Jan;206(1):261-9. DOI: 10.1148/radiology.206.1.9423681.

- Trimboli RM, Carbonaro LA, Cartia F, Di Leo G, Sardanelli F. "MRI of Fat Necrosis of the Breast: The 'Black Hole' Sign at Short Tau Inversion Recovery." Eur J Radiol. 2012 Apr;81(4):e573-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.06.048. Epub 2011 Jul 13.

- Ganau S, Tortajada L, Escribano F, Andreu X, Sentís M. "The Great Mimicker: Fat Necrosis of the Breast--Magnetic Resonance Mammography Approach." Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2009 Jul-Aug;38(4):189-97. DOI: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.01.001.

- Lee J, Park HY, Kim WW, Lee JJ, Keum HJ, Yang JD, Lee JW, Lee JS, Jung JH. "Natural Course of Fat Necrosis after Breast Reconstruction: A 10-year Follow-up Study." BMC Cancer. 2021 Feb 16;21(1):166. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-021-07881-x.