The United States has logged more measles cases in 2025 than in any year in more than three decades, potentially leading to the once-eliminated infectious disease to be declared active again.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released data on July 9, showing 1,288 confirmed measles cases, including the deaths of two children and one adult. Cases have been reported in 38 states, with most stemming from an outbreak in the Southwest that began in January in West Texas.

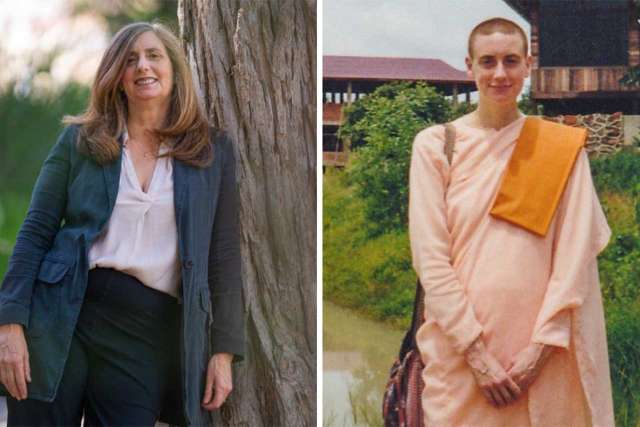

The increase in measles cases is multifactorial, says Sanchi Malhotra, MD, medical director of pediatric infection prevention for UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital and a professor in the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Vaccination rates declined during the COVID-19 pandemic and have yet to rebound to the 95% required for herd immunity, Dr. Malhotra says. There are also more measles cases circulating globally, and the highly contagious nature of the disease allows it to spread quickly.

Like COVID-19, measles spreads through airborne particles. But measles is six times more contagious, she says. One person infected with measles can infect up to 18 others in an unvaccinated population. With COVID-19, that rate was one to three. Furthermore, when someone with measles leaves a room, the room remains infectious for two hours as airborne particles remain in the air.

“It can be really hard to control from an infection-prevention and public health standpoint, given how contagious it is,” Dr. Malhotra says.

The best way to prevent measles is through vaccination. Before the measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, an estimated 3 million to 4 million people in the U.S. were infected each year, 48,000 were hospitalized annually and 400 to 500 people died, according to the CDC. Two doses of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine are 97% effective at preventing infection, it says.

“The measles vaccine is incredibly safe and effective,” Dr. Malhotra says. “It’s really our most effective tool to prevent measles, and it’s really responsible for the significant decline we saw in measles cases starting from when the vaccine was introduced.”

Nearly all the infections reported this year – 92% – were in people who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown. Of those infected, 4% had received one dose of the MMR vaccine, and 4% had received two doses.

Vaccination rates against measles are high in Los Angeles, Dr. Malhotra says. The California Department of Public Health requires children to receive two doses of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine before attending public schools.

Elimination status in jeopardy

Measles was declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, a distinction awarded by the World Health Organization after 12 months without disease spread. This status is likely to change if cases continue to increase. Public health officials in Texas predict the outbreak there will continue into 2026.

The last big measles outbreak in the U.S. was in 2019, when 1,274 cases were reported among Orthodox Jewish communities in New York. Last year, there were 285 cases reported nationwide.

Measles symptoms

Measles initially presents with cold-like symptoms – cough, runny nose, red eyes – before patients develop its characteristic rash. A person is contagious four days before onset of the rash, Dr. Malhotra says.

Some people will go on to develop pneumonia or a degenerative neurological disease. Measles can also affect immune cells, making them “essentially forget” immunity to diseases they were previously exposed to, she says.

“After a measles infection, kids tend to have more episodes of colds, diarrhea, other illnesses they might have already encountered because of measles directly affecting their immune system,” Dr. Malhotra says. “There are a lot of possible complications from measles. So it’s not just a benign disease. It actually can be quite scary.”

As of July 7, there have been 17 confirmed cases of measles in California this year, but they did not lead to outbreaks. Dr. Malhotra attributes that to high vaccination rates statewide. In some places in the U.S., vaccination rates are around 80%, she says, making those populations more vulnerable to measles spread.

Who is most at risk?

Young infants are particularly vulnerable to infection, as children typically receive their first dose of the MMR vaccine at 12 months old. However, infants who will be traveling internationally or visiting an outbreak area may be eligible to receive the vaccine at 6 months, Dr. Malhotra says, advising parents to speak to their pediatrician.

Immunocompromised individuals are also at higher risk of infection, but they should discuss with their physician if they may be eligible to receive the MMR vaccine, she says.

Measles vaccinations are typically provided free through the Vaccines for Children program.

Side effects of the measles vaccine include fever pain at the injection site. “The risk of complications with measles is significantly higher,” Dr. Malhotra says, “than any small risk from the vaccine, usually of a fever or a sore arm.”