It was around midnight when Carson Brooks jolted awake. He couldn’t breathe and felt he had no control over his body. His parents heard him retching and rushed into the then nine-year-old’s bedroom. They got him up from the bed and saw that his right leg dragged as he walked.

Fearing a stroke, they took him to UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center. But his vital signs were normal and after two hours of observation, they left the hospital. It was around 3 a.m. and Carson lay on his mother’s lap in the back seat.

Six blocks from home, he had a similar attack. They returned to the hospital where the physician witnessed another and admitted him. Carson was having seizures.

Pediatric neurologist Joyce H. Matsumoto, MD, diagnosed him with epilepsy and prescribed medication. A daily pill stopped the seizures, though every few months, Carson’s right eye would twitch with uncontrolled blinking.

Just before he turned 12, Carson was in the kitchen reaching for a plate, when he experienced a sudden seizure. He grabbed the counter to break his fall. The seizure lasted an excruciating 20 seconds.

Rather than outgrowing epilepsy, it seemed puberty had accelerated it. Over the next ten months, Carson spent more than 75 nights at the hospital. His epilepsy medications escalated to 28 pills a day, yet he was still seizing frequently. He missed school and baseball practice.

“I was a lot slower and processing things in school was harder,” said Carson. “It affected me a lot: my hand-eye coordination and agility, running slower.”

But his debilitating seizures ended soon after a device was implanted in his brain. Responsive neurostimulation (RNS) continuously monitors brain activity, detects an oncoming seizure, and delivers a small electrical current to prevent it. RNS has offered hope to the third of patients – like Carson – with drug-resistant epilepsy and is a fairly new option for pediatric cases.

“RNS has been a game changer in the epilepsy world,” said Dr. Matsumoto, who also practices at UCLA Mattel Children's Hospital in Westwood. “It has allowed us to offer a surgical option to so many more people than we could before.”

Carson called the device “life changing.” RNS and a second surgery to remove some of the affected area in his brain have led to far less intense seizures. His last severe one was August 1, 2018.

He’s down to 14 pills a day. And he recently moved into his dorm for his freshman year of college.

“I think the RNS saved his life,” said his mother, Tiffany Brooks. “It hasn't cured him of seizures, but his life is dramatically better than what it was before.”

Brain mapping

Seizures and headaches are the two most common conditions that Dr. Matsumoto sees in her clinical practice as a pediatric neurologist. “There's a lot of flux that's happening in a child’s developing brain and so it's just inherently more likely to develop irritation.”

A seizure can manifest when that irritation results in too much electrical activity in the brain. Epilepsy is when seizures are recurrent and unprovoked.

Other than the patient’s history and video evidence of seizures, Dr. Matsumoto’s main tool for diagnosis is the electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures electrical activity in the brain as wavy lines on a graph. She likened the “spikes” on the graph as sparks that could lead to fire: a seizure.

The EEG was crucial in helping to pinpoint where seizures were originating in Carson’s brain. The abnormal EEG activity showed that the affected area was the left side of his sensorimotor cortex. Further brain mapping revealed a likely congenital abnormality called cortical dysplasia – meaning the neurons in that area of the brain did not organize as they would normally.

“If you have a small area that didn't form correctly, the rest of the brain compensates and does its job,” explained Dr. Matsumoto, a health sciences clinical professor in the department of pediatrics at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “But that area is like a scar or mole. It’s part of your skin, but sometimes it can pull or itch. So that part of the brain is just a little irritable, and that irritability can then lead to seizures.”

Resective surgery to remove the affected area is sometimes a treatment option. But in Carson’s case, the location was too critical and would have meant losing motor function and sensation on the right side of his body.

“The RNS was created for people in Carson's situation because he had one focus that was in an area we couldn't take out,” said Dr. Matsumoto.

At UCLA Mattel Children's Hospital, neurosurgeon Aria Fallah, MD, MS, who is the co-medical director of the epilepsy surgery program, inserted electrodes into Carson’s brain. After seven days in the pediatric intensive care unit to map the source of the seizures in relation to areas of important brain function, it was time to decide whether to place the device. But Carson’s parents were initially reluctant, because the device had only been approved in adults so far – not children.

“Dr. Fallah came in and didn't promise anything other than: here's the facts, here's what we know, here's probability,” said Tiffany Brooks. “I believe in medicine; I believe in technology. And I trusted what Dr. Fallah and what Dr. Matsumoto were talking us through. The RNS was one of the best decisions we made in all of this.”

EEG downloads

Dr. Fallah performed a second surgery to implant the RNS device in 12-year-old Carson. The battery-run processor was placed into a small hollow of his skull. It was connected to a strip of four electrodes that lay on the surface of his sensorimotor cortex, while a second electrode went in deeper, behind the site of the improperly formed area.

“Responsive neurostimulation has opened doors for patients like Carson, where traditional surgery might have compromised critical brain functions,” said Dr. Fallah.

The device continuously monitors Carson’s brain activity. Dr. Matsumoto programmed it to recognize the onset of seizure activity and deliver a counteracting current. Determining the right level of current was a process of fine-tuning.

“You start low and go slow,” said Dr. Matsumoto. “There is a sweet spot where it can quell bad activity. But if you use too much, then you can also promote more irritability or cause side effects like they could feel the stimulation. Oftentimes that sensation will go away. It's like tightening your braces where you feel it for a bit, and then it will go away.”

In Carson’s case, too much current felt like pins and needles all over his body as well as a clicking noise. He is now at a level that has significantly reduced the intensity of his seizures, which are localized to the right side of his face, right arm and hand. The severe grand mal incidents he experienced previously have stopped.

Three years after the RNS was implanted, Dr. Fallah performed a resection surgery at the affected area that provided further relief. Carson had speech and occupational therapy for several months afterward.

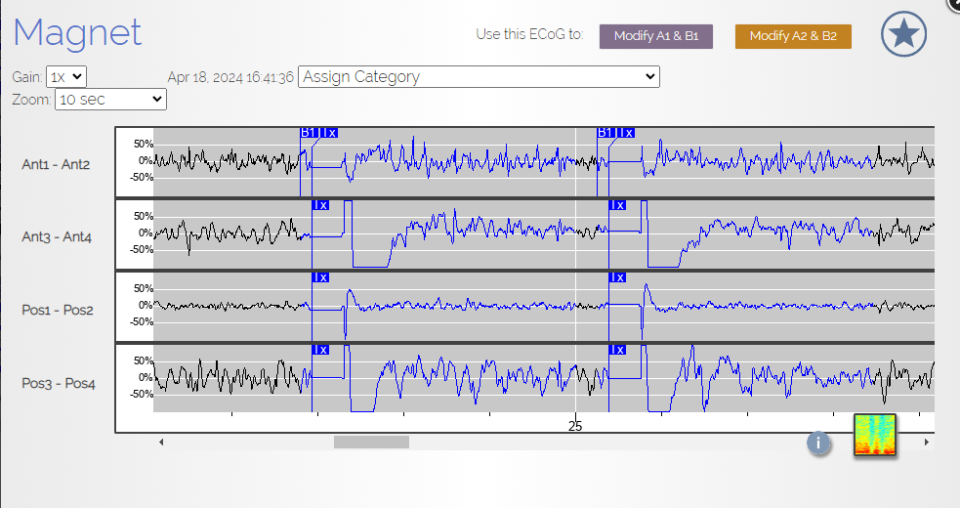

After that final treatment, medication and RNS are managing his condition. And the RNS can be re-programmed at any time. The device is also able to record snippets of EEG. Every evening, Carson waves a wand over the location on his head where the device is implanted (“My friends think I'm from outer space or something.”). This downloads the EEG data where Dr. Matsumoto can analyze patterns and make any adjustments.

Carson will stick with his daily downloads as he embarks on college life. He knows there will be road bumps along the way as he experiences a new setting and different levels of stress, which tend to aggravate his seizure activity. But he has developed coping strategies.

“I thought it would be good for me to have the college experience,” he said. “I know my parents are worried a little bit, which I understand because I am ‘seizure boy.’ But I think I'll figure it out within the next month or two for sure. I've been dealing with it.”

“Carson has had such a journey and he’s been very resilient through all of it,” said Dr. Matsumoto. “It shows how far he's come that he's maintained this goal to have the college dorm experience. I'm just so excited that he's going to be able to live it, and that we have finally gotten to a place where it's plausible.”