UCLA Health Mobile Stroke Unit: For when every minute counts

Time is brain, the saying goes, and for every minute that passes following a stroke, some 2 million brain cells die. When the call comes, UCLA Health’s mobile stroke unit hits the streets to get help to patients as quickly as possible, saving lives and preserving futures.

It was lunchtime, and Roberta Grady had just grabbed a sandwich and a cup of coffee during her volunteer shift at Calvary Chapel South Bay in Gardena when she collapsed. Someone dialed 911, and within minutes two ambulances arrived. One was the local paramedic. The other was a UCLA Health mobile stroke unit (MSU), a specialized rig with a compact brain scanner and UCLA Health stroke experts on board.

The first responders quickly determined that Grady was experiencing a stroke and brought her into the mobile stroke unit, where they immediately began the kind of diagnostic assessments and treatments that normally take place in a hospital’s Emergency Department. Inside the MSU, she underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan and CT angiography, which showed the precise location of the thrombus in the blood vessel that was impeding blood flow. Under the clinical direction of a UCLA Health vascular neurologist connected to the ambulance by state-of-the-art telemedicine, a nurse on board administered a thrombolytic medication to start breaking up the clot. Meanwhile, the MSU paramedic notified the closest, most appropriate center for stroke care that they were bringing an acute stroke patient who would need emergent, endovascular thrombectomy — a minimally invasive surgical procedure to remove the blood clot.

Within a half-hour of the stroke, Grady was undergoing treatment at Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center in Torrance.

Grady, 70, doesn’t remember the ambulance ride or the surgical procedure, but she clearly recalls walking out of the Torrance hospital on her own two feet eight days later, in May of 2024. She has since made a full recovery and is back to volunteering at her church.

“It’s because the mobile stroke unit was able to get to me as fast as they did,” Grady says. “I’m walking. I’m talking. I’m driving. I’m 100%.”

Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability, with associated annual costs in the tens of billions of dollars.

Time-to-treatment is critical. For every minute that passes following the onset of a stroke, 2 million brain cells die, says Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, director of UCLA Health’s Comprehensive Stroke and Vascular Neurology program. Though there are some 86 billion neurons in the human brain, studies show that a typical large-vessel ischemic stroke — one involving a clot, like Grady’s — kills 120 million neurons and 830 billion synapses an hour. In terms of normal neuron loss in brain aging, ischemic stroke ages the brain 3.6 years for each hour without treatment.

“With the mobile stroke unit, we can give the blood-vessel-opening thrombolysis drugs far earlier than if we have to wait until the patient arrives at the hospital,” Dr. Saver says. “This is a situation where bringing the hospital to the patient makes a tremendous amount of sense.”

A study published in 2021 in the New England Journal of Medicine found that treatment in a mobile stroke ambulance leads to better patient outcomes, both immediately and three months later. The study looked at data from seven urban centers in the United States and found that patients treated in a mobile stroke unit experienced less disability 90 days later compared with those receiving standard emergency medical treatment.

Nationwide, nearly 800,000 people experience a stroke each year — one every 40 seconds, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Around 87% of these are ischemic strokes, in which blood flow to the brain is blocked by a clogged artery or blood clot. The remainder are hemorrhagic strokes, which occur when a blood vessel in the brain ruptures and bleeds. Mobile stroke ambulances have the capabilities to treat both types.

Risk of stroke increases with age; studies show more than 70% of strokes occur in people 65 and older. Certain populations are also at greater risk. For instance, the risk for Black adults is nearly double that of white adults, according to the CDC. High blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, obesity and diabetes are all associated with stroke. One-in-three adults in the U.S. has at least one of these risk factors, the CDC says.

Stroke is a leading cause of long-term disability, with associated annual costs in the tens of billions of dollars. Stroke survivors may experience paralysis and difficulty with speech and cognition, as well as emotional challenges. Some people, like Grady, recover completely, while others experience ongoing disability. Quick treatment can make a huge difference.

For the nearly 15,000 Angelenos who each year experience a stroke requiring ambulance response, “the mobile stroke unit gives them the chance to be treated in the time frame when there is the most brain to save,” Dr. Saver says.

The world’s first mobile stroke unit hit the streets of Homburg, Germany, in 2011. Physicians are part of the emergency-response team there, and two doctors had the idea to install CT scanners in ambulances to expedite treatment for stroke patients.

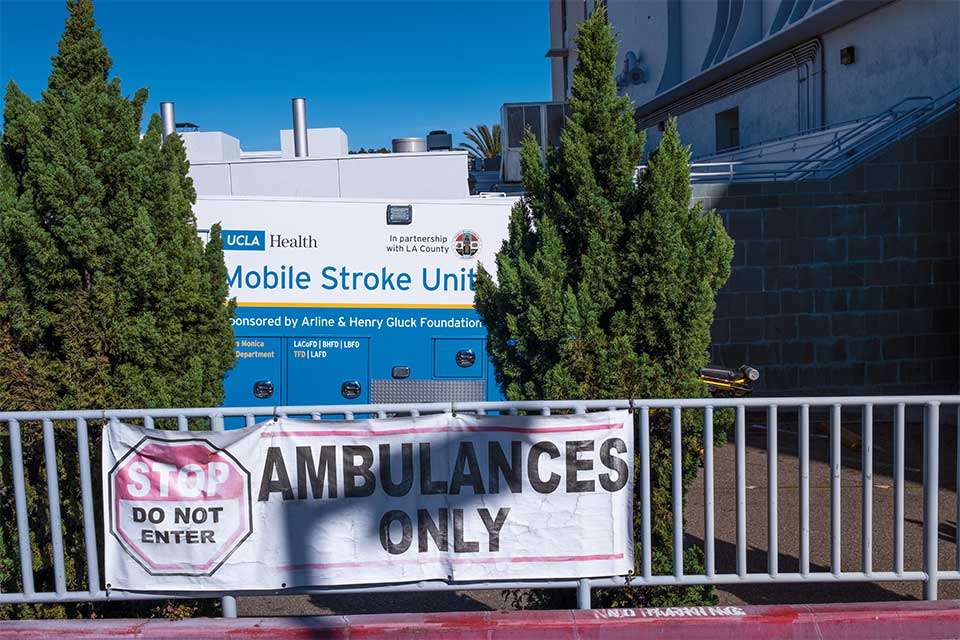

Three years later, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston established the first mobile stroke unit in the United States. UCLA Health launched its Mobile Stroke Unit Program — the first in the West — in 2017, with support from the UCLA Arline and Henry Gluck Stroke Rescue Program. Dr. Saver tapped May Nour, MD (RES ’13, FEL ’14, ’15), PhD, who had recently completed her fellowship in vascular neurology and interventional neuroradiology at UCLA Health, to build and direct the Arline & Henry Gluck Mobile Stroke Rescue Program.

This sent Dr. Nour on a deep dive into ambulance construction and understanding the web of emergency medical services that operate within Los Angeles County’s 88 cities and 140 unincorporated areas, devising how a specialized stroke ambulance could be used across the vast area, within different EMS rules and jurisdictions.

With support from the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors and Emergency Medical Services Agency, the first UCLA Health mobile stroke unit was designated a shared regional resource, working with fire department paramedics in Santa Monica, Los Angeles city and county, Torrance, Beverly Hills and Long Beach.

“That was an important milestone in being able to serve the citizens of the L.A. County community,” Dr. Nour says. It also helped complement stroke-specific training and stroke recognition for paramedics countywide, she says.

The partnership between UCLA and the local fire departments has been essential to the program’s success, says Kayla Kilani, RN, MPH, nurse manager of the mobile stroke unit. “Working together seamlessly ensures that we can get to patients as quickly as possible, deliver advanced stroke care on scene and truly make a difference in outcomes,” she says.

The mobile stroke unit rotates among participating agencies six days a week, spending a day or two responding to stroke calls that come via 911 at each. Though the unit is a program of UCLA Health, it is agnostic in its hospital response, bringing patients to 15 designated stroke centers across the county.

“We bring them to Kaiser hospitals, to Cedars-Sinai, to many different health care systems,” Dr. Saver says. “We’re operating as a service to the people of Los Angeles; our goal is to improve care for everybody.”

On a typical Friday at the Torrance Fire Department, firefighter-paramedic Mike Buchs monitors three radios, listening for calls indicating possible stroke symptoms: sudden numbness or paralysis on one side of the body, facial drooping, confusion, trouble speaking.

“We got a call,” he tells a visitor on a recent morning, while his UCLA Health colleagues — Curtis Morgan-Downing, RN, and CT technologist Lubna Mall, CRT — calmly but quickly head out to the rig, which is plugged in near the fire engines to keep its onboard CT scanner charged.

The mobile stroke unit responds to locations it can reach within about 20 minutes. Dr. Nour’s research determined this would allow the team to serve as many communities as possible within a 10-mile radius of each participating fire department. The Torrance team, for example, can reach stroke patients as far north as Inglewood, as far east as Carson and Compton and west to the South Bay beach cities.

Buchs, a 29-year Torrance Fire Department veteran, drives the rig, which is significantly heavier than an ordinary ambulance — the CT scanner alone weighs nearly 1,000 pounds. The vehicle is also equipped with cameras and computers to facilitate telemedicine connection with a vascular neurologist, who directs patient care in real time when not traveling with the team. Digital technology also allows for instantaneous transfer of CT scan results to remote physicians and receiving hospitals.

Diagnostic scanning onboard the ambulance is the game-changer in stroke treatment, Dr. Nour says. Symptoms can look the same whether a stroke is ischemic or hemorrhagic, but the in-ambulance treatment and level of hospital care required differ depending on stroke type. A patient experiencing an ischemic stroke can receive clot-dissolving medication en route to the receiving hospital. Patients experiencing a hemorrhagic stroke may receive drugs to reduce blood pressure and reversal agents for blood-thinning medications even prior to their arrival at a comprehensive stroke center.

“Accurate diagnosis in the field directs patients toward the most appropriate hospital,” Dr. Nour says. “Saving half an hour can make a difference in someone’s life, and afterward in someone’s quality of life.”

By the time the mobile stroke unit arrives on scene at a call, a traditional ambulance from the nearest fire department is usually already there. Paramedics from both units, along with the nurse or doctor from the stroke team, assess the patient. Are the patient’s deficits disabling? When was their last known well time? When did symptoms begin? The initial inquiry is about quickly assessing the patient so as not to delay care or the paramedics’ work, says Morgan-Downing, who has been working with the UCLA Health mobile stroke unit for two-and-a-half years.

The time since onset of symptoms is important because clot-busting medications for stroke can only be given within a strictly observed window. If too much time has passed, irreversible damage to the brain tissue will not allow patients to benefit from care and may lead to harm, Dr. Nour says. Every paramedic in L.A. County assesses potential stroke patients with the Los Angeles Motor Scale, which was developed by Dr. Saver and is used worldwide. It looks for facial droop, weakened grip strength and “arm drift,” or the inability to hold both arms up at the same level.

Within minutes, a patient who appears to be having a stroke can be inside the mobile stroke unit’s CT scanner, which resembles a large metal donut. The machine provides 3D images of what’s happening inside the patient’s brain and can reveal the precise location of a blood clot or area of bleeding. The scan takes about five minutes, says Mall, a CT technologist who joined the mobile stroke unit after decades working in hospital emergency rooms. She digitally transmits the images to the consulting physician, who can also observe the action inside the rig through its webcams. While the initial scan shows the tissue of the brain, a second scan performed with contrast reveals the health of the brain’s blood vessels and identifies blockages prior to the patient arriving at the hospital. Meanwhile, the nurse on duty establishes an IV line and begins administering the appropriate medication while traveling to the nearest stroke center.

With traditional ambulance response, none of these stroke-specific responses happen until the patient reaches the hospital. Studies show the UCLA Health mobile stroke unit treats patients on average 30 minutes faster in Los Angeles County compared to standard ambulance response.

“You may be seeing patients 15 minutes after the start of the stroke, when virtually the entire brain is still salvageable, and you have a chance to make a greater difference than you can in the hospital,” Dr. Saver says. “It’s very exciting.”

Buchs shares the story of one patient who was experiencing paralysis on half of his body when the mobile stroke unit arrived on scene. By the time they reached the hospital, after clot-busting medications had been administered, the patient was able to wave to the crew with his previously paralyzed arm.

Los Angeles County spans more than 4,000 square miles — too much area for a single stroke van to cover. Still, the UCLA Health mobile stroke unit has, since its launch, responded to more than 1,900 calls and treated more than 320 patients.

The need, however, is far greater. “Los Angeles is a big area, with 10 million people, and the one stroke unit that we’ve been using has been able to reach only a small fraction of them at any given time,” Dr. Saver says.

Dr. Nour envisions a day when mobile stroke units “are part and parcel of the fabric of EMS care across Los Angeles County.” To that end, she and her team created a geospatial map of where strokes occur most in the county so future units can be placed in areas of greatest need. The map shows seven-to-10 units are needed to cover the entire area, she says. “With the help of philanthropy, we’re now on our first step of expanding that fleet.” UCLA Health is launching two new mobile stroke vehicles in 2025, thanks to donations from a pair of Las Vegas-based philanthropists and their family foundations. (See “Rapid Responders,” page 18). One of these new units will be dedicated to serving the San Fernando Valley. The other will join the existing rotation of participating fire departments across the county. The new vehicles are equipped with state-of-the-art CT scanners that deliver faster imaging and higher image resolution, Dr. Nour says.

Having two additional units means “we’ll be able to position them in the stroke hot spots of the county,” Dr. Saver says. “We’ll be able to go to those areas where it’s most needed and ensure we can treat as many patients as possible.”

Philanthropy is essential to the Mobile Stroke Unit Program because most of the services it provides are not yet eligible for reimbursement through Medicare or other insurance carriers. Although the care provided by the unit is the same provided in a hospital, the novel setting means no billing “place of service” currently exists, Dr. Nour says. “This is a new paradigm.”

Dr. Nour envisions a day when mobile stroke units “are part and parcel of the fabric of EMS care across Los Angeles County.”

It is philanthropic funds and county support that make operation of the mobile stroke unit possible. The hope, Dr. Nour says, is that health insurance ultimately adapts to this new model, which a 2023 study shows is clinically effective for patients and cost-effective for health care systems. “Reducing debility and disability means reducing health care costs,” Dr. Nour says.

Both Dr. Nour and Dr. Saver say they’re proud to spearhead such innovative and effective care for stroke patients across Los Angeles County. “One thing that I really value is innovation, and also thinking outside of the box and building new infrastructures,” Dr. Nour says. “I was very fortunate to come upon this project — a project that bridges gaps between different groups of people and is very multidisciplinary, just like my training. This really fueled in me the ability to see how we can revolutionize the landscape of pre-hospital stroke care.”

Dr. Saver says the Mobile Stroke Unit Program “continues a long line of innovation in stroke care at UCLA.” Pioneering early studies of clot-busting thrombolysis drugs were done at UCLA, he notes, and the thrombectomy catheters that pull clots from brain arteries were invented at UCLA Health.

“Now we have the mobile stroke units bringing to patients both of those therapies more quickly,” Dr. Saver says.

These advanced approaches are worlds away from how strokes were handled when he first joined the UCLA Health medical staff in 1994. At that time, there was no established treatment for acute stroke. “Now, it’s a highly treatable neuro-emergency,” he says. “You have these Lazarus-like cases where patients come in with what in the past would have been a life-ending stroke and they walk out of the hospital because we’ve opened the artery in time.”

This was Grady’s experience. She thanks God that the mobile stroke unit was in her neighborhood the day she collapsed at Calvary Chapel. “Only God could do this kind of stuff,” she says. “It was the right day, right place, stroke unit on its way. They had the right medicine, and eight days later I walked out of the hospital.”

Sandy Cohen is a senior writer for UCLA Health Marketing Communications and a former national writer for The Associated Press.

More information about the UCLA Arline and Henry Gluck Stroke Rescue Program.