Note: This article was updated June 25, 2021 with new guidelines for lung cancer screenings.

Note: This article was updated May 25, 2021 with the new age guideline for colorectal cancer screenings.

UCLA Health provides cancer screenings that can save lives. In this guide, the health system’s leading experts explain the importance of cancer screening tests, who should get them and what to expect if results are abnormal.

“A lot of cancers are only treatable or are most treatable when they’re found early,” says UCLA Health internist Carol Mangione, MD, MSPH, vice chair of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, whose evidence-based screening recommendations are considered the gold standard.

“The whole goal of cancer screening is to detect cancers at a time when the likelihood of being able to cure them is higher, with the goal of preventing people from getting sicker and from dying earlier,” Dr. Mangione says. “We really want to use our screenings for people who are most at risk and will benefit most.”

Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer was once the deadliest cancer for American women, but cases and deaths have dropped significantly in the past 40 years because of screening, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“This has been an amazingly important and successful screening,” Dr. Mangione says. “You can save lives by screening for cervical cancer. Today, the majority of women who get cervical cancer have not been screened.”

Almost all cervical cancers are caused by certain types of human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection. Cervical cancer screening consists of either a Pap smear, a test for high-risk HPV, or both tests performed at the same time.

Cervical cancer rates are highest among women with the poorest access to screening, including some women of African-American, Latin American and Native American descent, and women without health insurance.

Testing process

During a pelvic exam, a primary care doctor, nurse practitioner or gynecologist gently scrapes from the cervix cells that are sent to a lab for examination. The method is the same for each type of testing. No special preparation is required.

Key findings

There are two major tests to screen for cervical cancer. A Pap test can reveal abnormal or precancerous cells. With an HPV test, cells are examined for the presence of types of HPV that increase the risk of cervical cancer.

Abnormal results

If a patient is screened only for HPV and the test is positive, the next step will depend on a patient’s age, whether she’s tested positive for HPV before, and for what strain of HPV is present. If a Pap test comes back abnormal, the patient may need a procedure called a colposcopy, which is a more detailed exam of the cervix through which cells can be removed for biopsy.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women should undergo their first Pap smear at age 21, with a screening every three years until age 29. HPV testing is not recommended for this group because often times when young women get infected with HPV, the infection resolves on its own without causing changes to cervical cells that could lead to cancer.

Women ages 30 to 65 have more options for types of testing, which may vary depending on what test is available at their doctor’s office. They can either continue with a Pap smear every three years or they can opt for HPV testing every five years, or undergo a combination of a Pap smear with HPV test every five years. Each option is considered equally effective.

Even young women who have received the HPV vaccine should undergo cervical cancer screening because there isn’t enough long-term data on the first generation of women to be vaccinated, Dr. Mangione says.

Women can stop screenings at age 65 if during the past 10 years they have undergone screenings as recommended and have had normal results.

Individualized screening plans may be recommended for women who have previously had high-grade precancerous lesions, as well as HIV-positive women who are at greater risk of HPV. The same goes for women who were exposed in utero to a synthetic estrogen called diethylstilbestrol (DES), which puts them at higher risk for cervical cancer.

Insurance coverage

Cervical cancer screening is fully covered by health insurance. Uninsured women can receive screenings through nonprofit community clinics or other safety net settings.

Colorectal cancer

Only 65% of Americans undergo screening for colorectal cancer, yet colonoscopies are among the most effective screenings because they simultaneously find and remove polyps that can cause cancer.

UCLA Health uses the colonoscopy as well as an at-home screening test, both of which seek to detect the presence of precancerous polyps, or growths, in the colon or rectum.

Offering both options leads to higher screening rates, says UCLA Health gastroenterologist Folasade May, MD, PhD, MPhil.

“The value of screening is incredibly high,” Dr. May says. “Luckily, we can prevent colon cancer in many cases by removing polyps.”

The home test, called fecal immunochemical test (FIT), looks for invisible traces of blood in the stool, which could be a sign of polyps or cancer. If blood is found, a colonoscopy must be performed.

Testing process

The FIT test requires a patient to remove a tiny stool sample from the toilet using a tool included in the kit. The sample goes inside a vial and is sent to the lab. No special diet or preparation is necessary.

For a successful colonoscopy, patient preparation is essential. The bowels must be thoroughly cleaned so any polyps are visible. The day before the procedure, patients consume a clear, liquid diet. In the evening, they drink a laxative that will trigger frequent trips to the bathroom. The laxative may be repeated again the next morning, prior to the procedure.

A patient will undergo either general anesthesia or conscious sedation at the hospital or surgery center. The gastroenterologist will insert a long, flexible tube with a camera and light into the rectum. The device also contains tools for removing polyps as they’re detected.

Key findings

The FIT test is highly sensitive but can miss the presence of polyps if they weren’t bleeding at the time. If it finds blood, which happens in 5% to 7% of tests, a colonoscopy is needed.

Most colonoscopies come back normal. The procedure offers a detailed view of the colon but 1% to 5% of colon cancers can be missed if a polyp is hidden in a fold. Removed polyps are examined by a pathologist who determines if a polyp is a higher-risk kind that is more likely to become cancerous. The type and size of polyps removed will determine the frequency of subsequent colonoscopy screenings.

Abnormal results

A colonoscopy is the only cancer screening that can both diagnose and treat, with polyps, including abnormal ones, removed during the procedure.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that colon cancer screening begin at age 45 for people with average risk and continue until age 75.

Patients with a family history of colon cancer should start at age 40, Dr. May says. Family history is defined as having a parent or sibling develop colon or rectal cancer before age 60 or two family members, such as grandparents, having had colon cancer at any age.

African Americans have the highest rates of colon cancer and the highest death rates so screening starting at age 45 is highly recommended. Patients who have inflammatory bowel disease that involves the colon should begin screenings 10 years after onset. So, if a patient is diagnosed at age 30, the first screening would take place at age 40.

As for which test to take, high-risk patients, including those with a history of polyps, should bypass the FIT and have a colonoscopy. Patients of average risk or those with significant barriers to undergoing a colonoscopy, such as lack of transportation or inability to miss work, can start with FIT if they prefer.

Latinos have the lowest rate of screening. Although Latinos are not more predisposed to develop colon cancer, they have poor outcomes because of lack of screening and late diagnosis.

If a colonoscopy finds high-risk polyps, a colonoscopy should be administered every three years. However, if the next screening comes back normal, the patient would come back in five years.

Patients with a family history should have a colonoscopy every five years.

Insurance coverage

Colon cancer screening is covered by insurance. However, due to a loophole in original Medicare, older patients who require polyp removal will be billed for a portion of charges. Access to colonoscopies is a major barrier for uninsured patients.

Breast cancer

The pink ribbon for breast cancer awareness is widely recognized, yet because of conflicting guidelines women may not know when to start mammograms or how often to have them.

Some doctors advise an annual mammogram starting at age 40 to catch as many cases as possible, while others say to test every other year starting at age 50 to reduce false positives and unnecessary biopsies. The American Cancer Society recommends annual mammograms beginning at age 45.

“We know that mammograms will save lives,” says UCLA Health breast surgeon Deanna Attai, MD, FACS. “It’s not a perfect tool, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have value.”

Dr. Attai recommends tailoring an approach with one’s doctor.

“We try and take a more risk-based approach, assessing family history of breast cancer, other risk factors and a patient’s risk tolerance,” she says. “Some patients may just feel more comfortable getting a mammogram every year starting at age 40 and are willing to accept the downsides.”

Testing process

During a mammogram, a technician captures two X-ray views of each breast. One at a time, a breast is pressed between two plates for a couple of seconds for a top-to-bottom and then a side-to-side view. The process is then repeated for the other breast.

Patients are instructed not to wear lotion or deodorant before the procedure because they can show up on the mammogram.

Key findings

The overwhelming majority of women will receive normal results. A radiologist reviews the breast anatomy images to look for suspicious lumps that can’t be felt. Calcifications in breast tissue can potentially indicate a pre-cancerous or cancerous process.

The test is less accurate for women with dense breast tissue, typically younger women.

Abnormal results

Depending on the findings, a patient might need more imaging, such as an ultrasound or MRI, or a biopsy.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening every other year from ages 50 to 74, although other groups recommend starting as early as age 40 or screening annually.

Women of average risk should discuss the pros and cons of when to start with their primary care doctors, although some doctors may follow a particular organization’s recommendations, Dr. Attai says.

For patients with a family history of breast cancer, screening decisions may depend on which relative was affected and their age at diagnosis. Generally, mammography would start 10 years prior to the age of the youngest relative’s diagnosis. So if a patient’s mother was diagnosed at 55, the patient would start at 40 or 45. If multiple relatives were diagnosed, especially at young ages, or if there is any male breast cancer in the family, genetic testing should be considered.

Low-income women and women of color face disparities in screening and cancer outcomes. For instance, Black women are screened less often than white women and are more likely to be diagnosed at a more advanced stage.

Annual screenings are recommended for women who have had breast cancer, who have a family history of breast cancer or have other risk factors such as genetic mutations.

Insurance coverage

Mammograms are fully covered by insurance. Uninsured women can get screened at nonprofit community clinics or by contacting groups such as Susan G. Komen.

Lung cancer

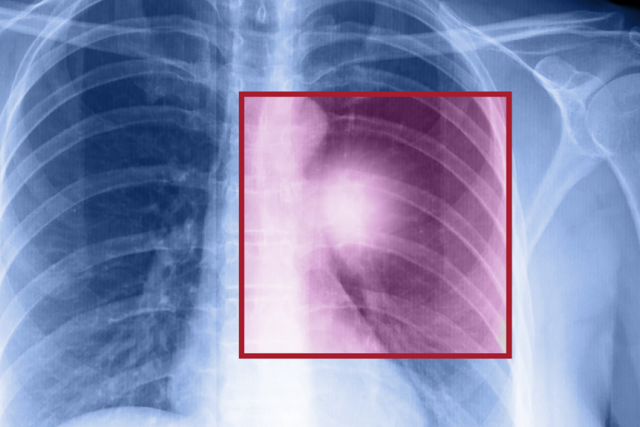

Lung cancer is the top-killing cancer among Americans, but certain high-risk people who have smoked, or currently smoke, can undergo a low-dose CT lung scan that reduces death rates by at least 20%.

“Lung cancer deaths exceed deaths from breast, prostate and colon cancer combined,” says Denise Aberle, MD, a diagnostic radiologist at UCLA Health. “We now have a screening test that can detect lung cancer in asymptomatic individuals, potentially at its earliest stage when local therapy can be curative.”

The test, however, has strict criteria for private insurance or Medicare coverage, and Dr. Aberle says sometimes doctors order screenings for patients who don’t qualify. She said patients should be referred to the UCLA Lung Screening Program to determine eligibility and to complete a shared decision making process.

Shared decision making includes a discussion of smoking cessation counseling, which is offered by UCLA Health, the harms and benefits of screening, counseling to ensure that patients understand that screening should be performed annually, and documenting that patients are willing to be treated for lung cancer if they are diagnosed.

Testing process

The screening exam itself requires no preparation. For the test, a patient lies on a scanner bed, with arms positioned overhead. The patient is moved into the “doughnut hole” of the scanner X-ray beam and instructed to take a deep breath to expand the lungs and hold for 5-10 seconds. The images are captured during those 10 seconds, using a lower dose of radiation than a typical CT scan.

Key findings

A dedicated chest radiologist examines nodules in the lungs for any that could be cancerous based on size and density of the nodule. Potential lung cancer is missed infrequently but the greater concern is a false positive for a nodule that is not lung cancer but requires further testing.

Abnormal results

Standardized guidelines have been developed by an expert committee in the American College of Radiology. UCLA Health follows those guidelines to manage lung nodules based on their size and consistency.

A large nodule could call for a biopsy or a PET-CT scan to look for cancer. Roughly 12% of all patients need some form of additional testing, but in the majority of cases, this only involves getting a follow-up low dose CT scan to ensure that the nodule does not change.

The UCLA Lung Screening Program has a dedicated Multidisciplinary Nodule Conference to review all screening exams in which a lung nodule requires follow up. Radiologists, pulmonologists and thoracic surgeons meet to determine the best strategy, Dr. Aberle says, although anyone can attend.

Screening guidelines

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force calls for screening people ages 50 to 80 with a history of smoking. To be screened, people who used to smoke, or currently smoke, must have smoked the equivalent of “20 pack years.” That means someone who smoked one pack a day for 30 years would qualify, as would a person who smoked two packs a day for 15 years. Former smokers should have quit within the past 15 years. A person who quit 16 years ago, for instance, would not be eligible.

African-American men are at highest risk, being 37% more likely to develop lung cancer. They have higher deaths rates than white men, despite smoking significantly less.

However, Dr. Aberle says, it is likely that starting next year, USPSTF guidelines will be changed to call for screening at a younger age – beginning at age 50 – and with a lower smoking intensity of 20 pack years. She says that would greatly help address the disparities faced by Black men by expanding their eligibility for screening.

A patient may need another low-dose CT scan in less than a year to check an abnormal nodule for any change.

Insurance coverage

Medicare patients are only eligible for screening until age 77. Private insurance covers the test until age 80. Patients without insurance should expect to pay about $250 for the screening.

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer screening has been controversial because some men who were diagnosed received treatment with side effects worse than their actual disease.

In 2012, the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommended that men no longer get a prostate-specific antigen or PSA test because of potential harms of treatment, such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction, for cancer that would never become symptomatic. However, since 2018 the group has said that men should, in consultation with their doctors, make individual decisions about screening.

Robert Reiter, MD, a urologist and director of the UCLA Health Prostate Cancer Program, said many of the downsides of overtreatment have been addressed. He encourages men to be tested and considers the PSA one of the best screening tests for cancer.

“The world’s changed,” says Dr. Reiter. “There have been a couple of very large screening trials showing that prostate cancer screening can reduce the risk of death from prostate cancer from 20% to 30%. We’ve become much better at figuring out who needs treatment and who doesn’t, so the risk of over-diagnosis leading to overtreatment has lessened.”

Additionally, Dr. Reiter says that during the years when men were advised against PSA testing, the percentage of patients with metastatic prostate cancer increased dramatically.

Testing process

The PSA test consists of a simple blood draw to measure a normal protein made by the prostate. No preparation is required.

Key findings

Doctors analyze the PSA result based on age, change over time and relative to the size of the prostate. Most men with an elevated PSA don’t have prostate cancer. The screening will pick up 80% to 90% of men who do.

Abnormal results

An MRI of the prostate would be performed or additional blood and urine tests. Dr. Reiter says the goal is not just to find cancer but rather to find cancer that poses a threat.

Screening guidelines

The USPSTF now recommends that screening for men ages 55 to 69 be a decision between a patient and his doctor.

Dr. Reiter says he generally recommends a PSA screening by age 50, with testing to be done every one to two years. He says some patients should be screened earlier. If a patient has a brother or father who had prostate cancer, he should be screened starting at age 40. The same applies for men with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer, because aggressive prostate cancer is associated with BRCA2 genetic mutations.

African Americans are at higher risk of developing and dying from prostate cancer and should get an initial screening at age 40 or 45. If a Black man, or a patient with a family history, gets back a normal result with a first test, he can wait until age 50 to resume testing.

As for when to stop, Dr. Reiter says he would screen patients up to age 75 if they were likely to live more than 15 years.

Screening intervals may be adjusted based on PSA results.

Insurance coverage

Medicare and private insurers cover PSA testing. Uninsured men can contact nonprofit community clinics, which in some cases offer mobile testing.

Courtney Perkes is the author of this article.