Cognitive impairment isn’t often discussed as a side effect of cancer treatment, yet many people experience thinking and memory challenges during the cancer journey and, for some, these issues persist into survivorship.

“It’s still an ongoing effort to be sure that these types of symptoms and issues are getting the attention that they deserve and the treatment that they deserve,” said Kathleen Van Dyk, PhD, a neuropsychologist at UCLA Health who hosted a recent webinar for the Simms/Mann UCLA Center for Integrative Oncology called “Cognitive Impacts After Treatment.”

The Simms/Mann Center provides free psychosocial support to people receiving cancer treatment at UCLA Health.

Studies show that as many as 75% of people undergoing cancer treatment experience cognitive changes, and about 25% of them may experience lasting problems after treatment is complete, Dr. Van Dyk said.

While it’s difficult to pinpoint who exactly will experience cognitive challenges from cancer treatment, knowing that these issues are common and talking about them with a provider can better prepare individuals to know what to expect, she said: “It shouldn’t be surprising to patients that when they try to go back to work … that they’re not functioning the same way that they used to, because that can be really disheartening.”

What causes cognitive issues during cancer treatment?

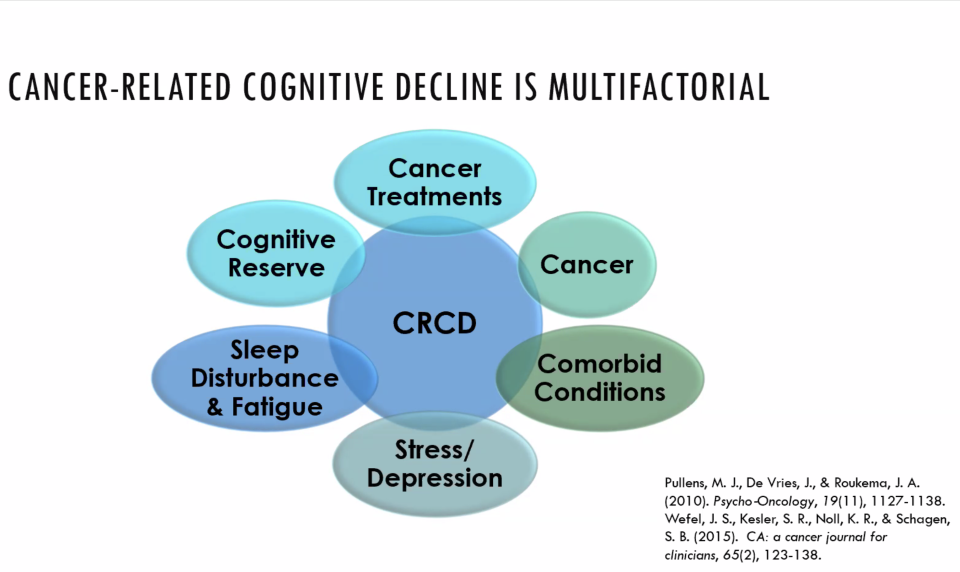

Scientists don’t know exactly how cancer treatment can cause cognitive changes. Chemotherapy, radiation and drugs such as tamoxifen have been shown to contribute to such changes. The toxicity profile of different cancer treatments and whether those treatments cross the blood-brain barrier, which defends the brain from toxic substances, are also factors, Dr. Van Dyk said. The body’s response to cancer itself may also contribute, she said.

Neuroimaging studies show changes in gray matter volume in the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex after chemotherapy. Other studies show changes in white matter, which affects brain efficiency.

In some individuals, “it looked like the brain was using more energy to do the same task after chemotherapy compared to the brain of someone who did not get chemotherapy,” said Dr. Van Dyk, who is also a member of the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

A person’s life circumstances before cancer treatment also affect cognition. Comorbid conditions and other health problems may weaken resilience to cognitive changes during cancer treatment, Dr. Van Dyk said.

Stress and depression also play a significant role in cognition, even in people without cancer.

“Higher levels of stress and higher levels of depression can certainly contribute to having worse cognitive functioning day to day,” Dr. Van Dyk said.

Sleep disturbances, which are common during cancer treatment, are also known to contribute to cognitive problems.

What kinds of cognitive challenges may cancer treatment cause?

Patients may feel like tasks take more mental energy than they used to, Dr. Van Dyk said. They may have trouble recalling names, facts and details, or finding the right word – what she called “tip-of-the-tongue syndrome.” Some patients say they’re not as sharp as they used to be, she said, or that “the edge is gone.”

Cognitive challenges related to cancer treatment “rarely look like something as severe as dementia or Alzheimer’s disease,” she said. “But the impact of even subtle changes in the context of cancer treatment is still quite profound.”

Many people first notice these changes when they return to work after treatment.

“They go back into the office, or wherever their workplace is, and they can't jump back in and perform exactly the same way they used to,” she said. “They're not as productive, their memory isn't quite the same, they're not as efficient, they're more tired. There's a lot more fatigue.”

She advises patients to gradually ease back into work if possible, taking on fewer or easier projects at first. It may help to seek support from supervisors and Human Resources.

Four cognitive domains affected by cancer

Dr. Van Dyk offered strategies for dealing with the four cognitive domains most commonly affected by cancer and cancer treatment: attention, executive function, memory and language.

Attention is being able to work under distracting conditions – filtering out unnecessary information and filtering in what you need to focus on. Walking into a room and forgetting what you went in there for is often more of an attention issue than a memory one, Dr. Van Dyk said: “We’ve lost the attentional thread that we were on.”

To increase focus, she advises cleaning off your desk – both your physical desk and your computer desktop – so it’s easier to stay focused on the task at hand. Close unnecessary computer windows, turn off notifications and silence your phone. Schedule time to answer emails rather than replying to each message that comes in and let your colleagues or family members know you need some uninterrupted time.

Dr. Van Dyk also encourages patients to talk to themselves – “not out loud, if that’s weird” – but to have a dialogue with themselves to help hold onto their attentional thread. So, for example, if you’re going downstairs to get a glass of water, you might repeat your mission to yourself in your head until you complete the task.

Executive function is the ability to plan, prioritize, organize and adapt. Reasoning, judgment, decision-making and multitasking are all aspects of executive function, Dr. Van Dyk said. In everyday life, tasks that call on this cognitive dimension include setting up a budget, planning a trip or event, organizing a weekly schedule and meal planning. Cooking, itself, is often a complicated task, she added, requiring management of ingredients, steps and measurements.

To support executive function, Dr. Van Dyk advises making checklists – taking information out of the brain and putting it in a document somewhere. Define the task and its elements and steps and write them down, adding to the list as needed and checking things off as they’re completed. She also recommends a strategy called “Stop. Think.” Sometimes she tells patients to imagine a stop sign and allow themselves a moment to reorient to what’s happening, asking themselves: What was I just doing? What do I need to do? Should I maybe write out my next steps?

Memory is about receiving information, learning and encoding it and being able to retrieve it when we want it. Dr. Van Dyk said her patients undergoing cancer treatment report that it’s harder for them to learn new things or access information they need.

“They might have forgotten something that used to be pretty routine for them,” she said.

Again, Dr. Van Dyk advises writing things down: enter it on your calendar, put it in your phone, carry a notebook. “Use your external sources of information to record what maybe might be a little bit harder to remember,” she said.

Her trick for remembering names of new people is to repeat the name as soon as you hear it – “Nice to meet you, Kim” – and then to make mental associations with the name: Do you know any other Kims? Maybe you think of your cousin Kim and how they both have brown hair. When you leave the person, use their name again: “Great talking to you, Kim.”

Language issues – word-finding difficulties – are among the most common complaints Dr. Van Dyk’s patients share, but these challenges don’t point to any loss of vocabulary, she said.

The brain organizes words into semantic groups, she explained: “We have these networks in our brain where there are words that kind of share some sense of meaning with each other.” For example, the word “elephant” might live in a network that includes gray, trunk, zoo, monkey, giraffe. So when we can’t pull up the word “elephant,” we can often find associated words: It’s gray, it has a trunk, there’s one at the zoo.

“The word is still part of your vocabulary,” Dr. Van Dyk said. “In that moment, things are a little bit fuzzy and accessing that particular word is a little more challenging.”

For many patients, the frustration of not being able to pull up the word they want can make it difficult for them to continue expressing their idea, she said, but she reassures them that it will come back to them and suggests they use associated words to make their point.

Word exercises – coming up with synonyms, antonyms, homonyms and rhyming words – can help strengthen semantic networks, Dr. Van Dyk said, as can reading aloud.

Practice stress reduction

Ultimately, when any of these cognitive challenges arise, Dr. Van Dyk advises practicing self-compassion. Other stress-reducing practices, such as snuggling with a loved one or pet, or visualizing a beautiful place, can also make it easier to deal with cancer-related thought and memory issues.

“Staying in touch with those things that bring you joy and that fill your spirit are very relevant, not only to cognition, of course, but quality of life in general,” Dr. Van Dyk says. “So giving yourself the time to read, to exercise, to take some time off from a busy day can certainly be a big component and a big boost to cognitive function.”