Chronic Total Occlusions and Treatment

Find your care

Interventional cardiology teams provide care in multiple locations. To learn more about our services, call 310-825-9011.

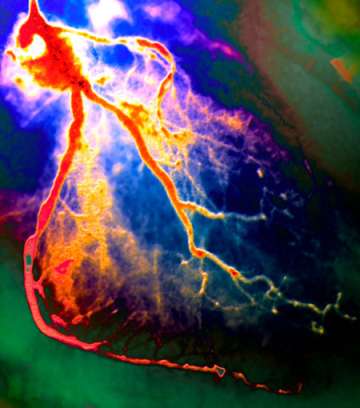

Outcomes for Chronic Total Occlusions Improve

Using advanced technology and specialized training, UCLA interventional cardiologists are improving outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with chronic total occlusions of the coronary vessels. Ravi Dave, MD, director of interventional cardiology at UCLA , explains how a small number of centers are taking advantage of the new technology to advance treatment for a challenging problem.

What is meant by a chronic total occlusion of the coronary arteries, and how do CTOs develop?

CTOs are 100-percent obstructions of coronary arteries that have been present for more than three months. Typically, there is no downstream blood flow from the main lumen of the artery. They tend to develop in one of two ways. It can be as a silent heart attack, in which the patient experienced symptoms but didn’t seek care, or the symptoms were so weak that he or she didn’t realize what was happening and only later it was discovered on an angiogram. The other way of developing a CTO is that a blockage progresses over time — going from 70 to 80 to 90 to 100 percent. When it gets to that point, the patient may or may not have any symptoms.

How commonly are CTOs discovered on a coronary angiogram, and what is the urgency of treating them?

In 10-to-20 percent of angiograms, patients have no blockages at all — the stress test was falsely positive or it turns out their symptoms are unrelated to the heart. Patients with blocked arteries undergoing a coronary angiogram have up to a one-third incidence of having a CTO. In terms of the urgency, some studies have shown that if you leave the CTOs untreated, these patients can have more damage to the heart muscle, potentially leading to congestive heart failure and a higher three-year mortality. On the other hand, successfully reopening a CTO in the presence of a viable heart muscle has been associated with improvement in symptoms, left ventricular function and survival.

How has the approach to CTO treatment changed?

The way we are opening these blood vessels is completely different from what we were doing before. Previously, the focus was to go through the lumen of the artery and re-enter past the blockage. Now, we are much more comfortable creating a diversion within the wall of the artery. The artery wall has three layers, and sometimes the blockage in the lumen of the artery is so tight that the wires can’t poke through. So we create a breakage in the layers of the wall, then we go in and re-enter downstream of that 100-percent blockage. Once we’ve created that small diversion, we place a stent. So, instead of the artery running straight, we would turn a bit to the left, run parallel, turn back right and re-enter the artery.

What is required to perform this procedure?

It’s a complex angioplasty procedure that is not something every center can do. You need to have special training and specific technology. This includes special types of wires and balloons to negotiate through and open the 100-percent blockages. At UCLA, we have dedicated ourselves to the training and technology, and it has led to significant improvements.

How has this affected patient outcomes?

Before we had this technology, the rate of success at reopening CTOs nationally was less than 50 percent, and at UCLA it was about 60 percent. Now, with this combined percutaneous approach, our success rate at UCLA is more than 85 percent.

Which patients are candidates?

Any patient with a chronic total occlusion who has symptoms, or who has an abnormal stress test suggesting a reduced blood flow, may be a candidate. We don’t necessarily go after every CTO. We determine whether it’s causing the patient to have reduced blood flow in an area of the heart that’s not adequate, and the heart muscle has to be viable in that area. But if that’s the case and you open the blockage up, it has been shown that the patient’s symptoms improve, heart muscle function improves and patient survival goes up.

This article originally appeared in Physicians Update Spring Edition 2015