Sabrina Cheung began to involuntarily spin in circles, to the right, when she was 4.

Although her parents, Gilbert Cheung, MD, and Judy Liu, MD, are both radiologists, they were not familiar with her symptoms and sought a diagnosis. A neurologist performed an electroencephalogram (EEG) – a test that measures brain activity – which showed that Sabrina was having seizures.

She was diagnosed with epilepsy in 2012.

Over the next month, Sabrina’s seizures increased from one or two a week to around 40 seizures a day. She was referred to an epilepsy specialist, was put on three to four anti-seizure and depressant medications, and was restricted to a ketogenic diet, high in fats and low in carbohydrates. Sabrina’s meals required 4 grams of fat for every 1 gram of carbs.

Sabrina’s seizures decreased to two to seven daily, lasting around 15 seconds. Instead of spinning, she would fall backward and be sleepy afterward. She required an adult nearby during all waking hours to prevent injury.

Sabrina’s quality of life was significantly impacted, too. She was failing the second grade and would fall asleep throughout the day.

“She was basically a zombie, because she was on so many drugs and couldn’t complete basic tasks like brushing her teeth without repeated prompts,” Dr. Cheung said.

A difficult catch

Four years after Sabrina’s diagnosis, she was getting prepped to have a vagal nerve stimulator implanted in her neck. The device sends electrical impulses to the brainstem to calm irregular electrical activity, but it does not treat the underlying lesion that causes seizures.

The device reduces seizures by half in 50% of patients, but Dr. Cheung took his daughter to UCLA Health hoping to find a different treatment option with a greater success rate. “It was a last-ditch effort, we didn’t really have high hopes,” he said.

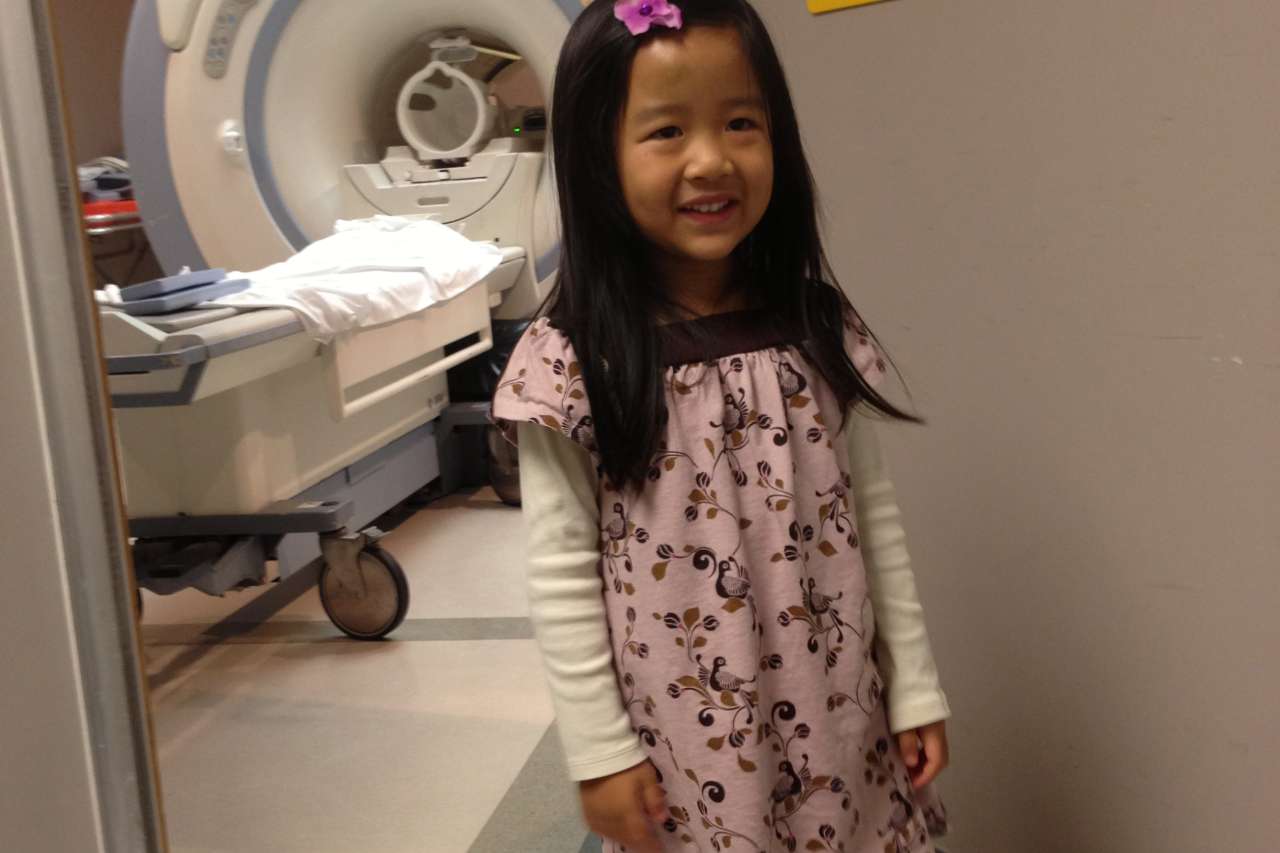

In 2016, Sabrina met with Noriko Salamon, MD, PhD, a neuroradiologist at UCLA Health, who had her undergo a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to get detailed images of the brain.

The combined scans are common now, but at the time, Dr. Salamon was one of the first doctors to employ the approach.

“Multi-modality is a buzzword, but it took years of research to combine using a PET scan, which reveals function, and an MRI scan, which reveals the anatomy of the brain,” Dr. Salamon said. “Most doctors didn’t use both technologies at the time because it was just too complicated.”

Applying her attention to detail and understanding adjacent fields such as nuclear medicine and neurosurgery, Dr. Salamon was able to find a malformation in Sabrina’s left frontal lobe on her PET scan, even though initial readings detected no abnormalities. Dr. Salamon then confirmed the location of the subtle lesion with a follow-up MRI.

“I’m a radiologist and I don’t read PET scans, but Dr. Salamon goes that extra step to fully understand what departments she’s collaborating with are doing,” Dr. Cheung said. “Dr. Salamon’s detection of this extremely subtle abnormality is like a baseball player making a difficult catch while jumping into the stands to save a game.”

Dr. Salamon goes above and beyond in clinical care because she’s driven by the mysteries of the unknown. “I’m motivated by curiosity,” Dr. Salamon said. “That’s why I picked epilepsy as my sub-specialty – there's still so much that we don’t know about the brain.”

Changing the trajectory of Sabrina’s care

After Dr. Salamon identified the brain lesion that was causing the seizures, Sabrina was taken to UCSF to undergo a magnetoencephalography (MEG) exam to confirm the location of the lesion. Sabrina then went to the University of Washington to have her lesion surgically removed.

“If Dr. Salamon didn’t find the lesion, Sabrina wouldn’t have gotten surgery,” Dr. Cheung said.

Prior to the surgical resection, Sabrina’s seizures had escalated to screaming, falling, and kicking. But afterward, Sabrina did not have a seizure for nearly two years.

“She woke up and immediately started functioning in and outside of school,” Dr. Cheung said.

Returning to UCLA Health

In 2019, however, Sabrina started to have seizures again, but they were less severe and less noticeable.

“It’s a four- to five-second interruption,” Sabrina said. “I’m aware it’s happening, and then I resume whatever activity I was doing.”

Now 16, Sabrina has been able to join her high school swim and water polo teams, and has already taken the SAT. Although her seizures are much less severe, she continues to see epilepsy specialists at UCLA Health.

“She will likely undergo a craniotomy, where doctors take off part of the skull and put an EEG grid on the brain surface to monitor her seizures,” Dr. Cheung said.

The doctors may use laser ablation to treat the area causing seizures, or they may implant a brain device that fires electrical pulses to counteract the onset of seizures. This treatment is called responsive neurostimulation.

At Sabrina’s next appointment, the epilepsy specialist will determine next steps.

“I feel anxious about Sabrina’s potential procedure, but I also feel reassured after talking to Dr. Salamon and other epilepsy specialists,” Dr. Cheung said.