Melanomas aid themselves in their quest to spread to other parts of the body by sending a chemical signal to the sentinel lymph node, the node most susceptible to early spread of the cancer. The signal cripples the sentinel node's immune response, making it more vulnerable to the cancer, UCLA researchers discovered.

However, UCLA scientists were able to reverse the immune suppression by injecting patients with a compound that stimulates an immune response in the node. The discovery, outlined in the recent issue of Nature Reviews/Immunology, provides valuable clues about how melanomas spread and may one day lead to new ways to treat this deadly form of skin cancer, which will strike more than 62,000 Americans this year. About 8,000 will die from the disease.

"Our success in engineering a reversal of the immune suppression may lead to ways to protect melanoma patients before their cancers attempt to spread," said Dr. Alistair Cochran, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and surgery, a researcher at UCLA's Jonsson Cancer Center and lead author of the study. "The restoration of the sentinel lymph node to its normal state should make it better able to fight the spread of cancer."

A new treatment would be a valuable tool for oncologists. Most melanoma patients undergo surgery, but few other treatments have proven effective against this aggressive cancer, Cochran said. Chemotherapy doesn't help much, nor do hormonal or vaccine treatments.

"Right now, we don't have much to offer patients besides surgery," Cochran said. "While it doesn't affect as many people as breast and prostate cancer do, the numbers of melanoma cases are increasing faster than any other type of cancer and the population affected is expanding beyond the traditionally susceptible Caucasians."

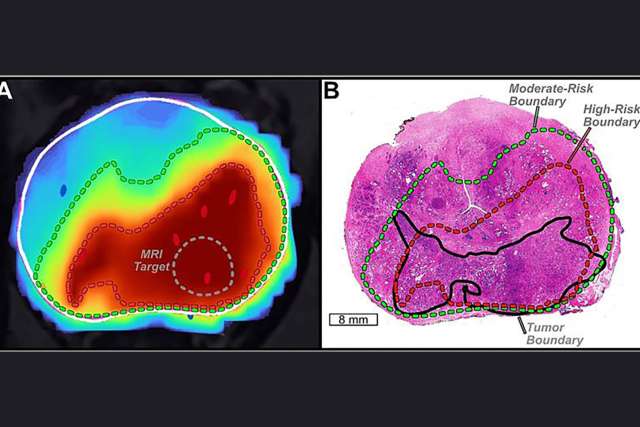

Lymphatics and lymph nodes serve as a drainage system for the tissues. A complex network of lymphoid organs, lymph nodes, lymph ducts and lymph vessels transport and filter lymph fluid traveling from tissues to the circulatory system. The sentinel lymph node is the first lymph node or group of nodes reached by lymph-borne metastasizing cancer cells from a primary tumor. It plays a critical role in the spread of cancer, limiting or channeling the malignant cells to other lymph nodes as well as other parts of the body where they can take hold and grow.

Cochran and his team found that the sentinel node, modified by the influence of the primary tumor, can, in turn, transfer tumor-induced immune suppression to other lymph nodes downstream, the effect hop-scotching along the system until all the nodes become more vulnerable to the cancer. If the process can be reversed at the sentinel node, the cancer may be prevented from spreading at all.

Cancer is most treatable when it is caught early and has not yet spread. Most people who die from cancer succumb when the disease spreads, Cochran said. About 20 percent of melanoma patients have cancers that will spread. In the past, many patients opted for prophylactic removal of all the lymph nodes near their tumor, a procedure that prevented the spread of the cancer but carried with it complications such as limb pain, reduced mobility and swelling. And since only about 20 percent were at risk of their cancer spreading, about 80 percent were undergoing a major procedure they didn't really need.

The practice now is to remove the sentinel lymph node when the patient's tumor is removed and test it for cancer. Patients with a sentinel node that tests positive for cancer usually have all the nodes in the immediate area removed because there's a more than 30 percent chance there already is cancer in the other nodes. If no cancer is found in the sentinel node, a patient can be confident that the risk of recurrence is small, Cochran said.

Cochran said the discovery of how melanoma disables the sentinel lymph node is leading to further studies that will more closely examine what is happening. They hope to confirm that rescuing the sentinel node and restoring it to normal function will make it more difficult for the cancer to spread.

"Until more effective chemotherapeutic agents become available, local and regional biotherapy to modulate the tumor micro-environment is an interesting and potentially effective approach to the non-surgical management of solid malignancies," the study concludes.

Melanomas Cripple Lymph Node Immune Function so They Can Spread to Other Parts of the Body

Related Content

Articles:

Services:

Related Articles

December 12, 2025

5 min read

December 11, 2025

4 min read

December 11, 2025

3 min read