About nine months into the COVID-19 pandemic, Jane Fazio, MD, began to question her future in medicine. She was in her first year of a pulmonary-critical-care fellowship at UCLA when her chosen career path began to feel unsustainable, like it was taking more from her than she could give. After months spent in the hospital system’s ICUs caring for patients critically ill from COVID-19 — watching as many shared final words with family over Zoom and then died alone in their hospital beds — and working too long and sleep - ing too little, she was exhausted and depleted.

She also was among the more than 910,000 health care workers in the United States to contract COVID-19.

Despite being young and healthy, Dr. Fazio worried that she, too, could die. “It felt like the only COVID patients I had ever seen were the ones who were dying,” she says. “The emotional impact of having COVID and going right back to the same thing, I think that was probably the worst. I started feeling like, ‘I cannot do this anymore.’”

Like so many health care workers, she was experiencing burnout — what the American Medical Association defines as a long-term stress reaction characterized by a sense of detachment, emotional exhaustion and negative feelings about work, patients and personal achievements

“At one point, I was asking myself, ‘Why am I doing this?’ This is a choice. I don’t have to be a critical-care doctor,” Dr. Fazio recalls. “And I just started to think, I’m going to quit, and what will I do if I quit?

Pandemic-related burnout among health care workers has become a national crisis, one that is receiving attention from the popular press, as well as academic journals, across the country. “U.S. Faces Crisis of Burned-Out Health Care Workers: Hospital leaders are sounding the alarm as health systems face an exodus of ex - hausted and demoralized doctors, nurses and other front-line workers,” shouts a headline in U.S.News & World Report. “Why Health-Care Workers Are Quitting In Droves,” reports The Atlantic. AAMCNews, the online magazine of the Association of American Medical Colleges, published an opinion piece titled, “Medical burnout: Breaking bad.”

Finding solutions to this problem now is a priority for such organizations as the National Academy of Medicine, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of the Surgeon General.

Even before the pandemic intensified workloads and exacerbated stress levels in hospitals and health clinics across the country, 79% of physicians reported feeling burnout, according to the CDC. “The pandemic has really highlighted to us that if we do not take urgent action, then our health care workers will continue to suffer, and the entire health care system will be under threat,” said U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, during a presentation last year about the emotional state of the nation’s health care workers.

Dr. Murthy’s concern is borne out in a survey conducted in October 2021 by the research firm Morning Consult, which reported that nearly one-in-five health care workers have left their jobs since the pandemic began. Another 31% have thought about leaving their employers, including 19% considering leaving health care altogether. (In an earlier Morning Consult survey, 46% of health care professionals said their mental health has deteriorated during the pandemic.)

Another study, by researchers at the University of Washington published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, found that half of health care workers surveyed were reconsidering their occupation because of the pandemic.

“Depending on which survey you read, 60-to-75% of health care workers are experiencing symptoms of exhaustion, depression, anxiety, insomnia and even PTSD,” says Victor Dzau, MD, president of the National Academy of Medicine. “This was a problem to begin with, and COVID has made it much worse.”

The stress of the pandemic has put additional pressure on an already strained national health care system that is short on medical professionals: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts a need for 1.1 million additional nurses in 2022 to meet health care demands, and the Association of American Medical Colleges forecasts a shortage of as many as 48,000 primary-care physicians and 77,100 specialty physicians in the next dozen years. From the start of the pandemic, the leadership of UCLA Health recognized the emotional toll the health crisis could take on its frontline physicians and staff. “This has been an unprecedented situation for health care providers nationwide,” says Johnese Spisso, MPA, president of UCLA Health and CEO of UCLA Hospital System. In an open letter to all staff written early in the pandemic, she said: “To get through it we must continue to care not just for our patients, but also for each other as well as for ourselves.”

In response, UCLA Health launched a number of initiatives, including counseling and wellness programs, to help staff deal with the daily stresses of the pandemic and the burdens, both professional and personal, that it was creating. “We support the health and well-being of our health care workers as they navigate through the pandemic and continue to provide exceptional patient care,” Spisso says. “We know that the last two years have taken a toll on our staff and their families, and we continue to be committed to offering ongoing support.”

Borrowing from a colleague’s vivid description of the pan - demic, Karen Grimley, PhD, MBA, RN, chief nurse executive for UCLA Health, called it “the longest, slowest mass-casualty event in our history.” Hiring more health care workers has been a key priority; Dr. Grimley expects to have added nearly 500 nurses by January 2022. “If I don’t have the right number of people in the units and clinics caring for the patients, I can’t start offering nurses the time and resources they need to decompress and begin to care for themselves,” she says. “First, we have to have the foundation in place.

As the pandemic has unfurled over the past two years, the stressors confronting health care workers have multiplied.

Initially, there was widespread fear and uncertainty and global shortages of personal protective equipment. Patient intake soared by unprecedented numbers, and so, too, did deaths. Each patient lost to the pandemic further ate away at the morale of those working so hard to save them. Nathan Yee, MD (FEL ’21), a critical-care physician at UCLA-Harbor Medical Center, recalls a COVID-19 patient he cared for during the final year of his fellowship at UCLA who went home and was doing well after a long hospitalization in the ICU, only to suffer a cardiac arrest and die. “It was story after story like that for months,” Dr. Yee says. “These stories have taken a piece of my soul that I don’t think I’ll ever get back. Like many of us, I’m certain I’m going to emerge a different person when this is all said and done, hopefully for the better, but who knows.”

Around the country, staffing levels have been further stretched as workers, no longer able to bear it, resigned or retired, or got sick with COVID-19. Vaccines simultaneously offered a new measure of protection and a new sense of national division along political and philosophical fault lines.

The cumulative burden of the pandemic has been overwhelming: the fear that has permeated hospitals and the strain of isolation at home; the unfairness of the disease and the toll it has taken on communities of color that disproportionately have borne the brunt; the sheer volume of patients a nd de at h s d r iven by each recurring surge and, now, the evolution of new variants; and the politicization of the virus that has led some people to distrust science and disregard common-sense protective measures to curb the spread.

It took nine months for that cumulative burden to break Tatiana Johnson, RN. It was more than the sadness of so many deaths witnessed in the COVID ICU, the daily stress of being an emotional bridge for family members who couldn't be close to their loved ones and the fear of catching the virus and spreading it to her friends and roommates. “A huge part of how I'm able to be a good nurse is having the time to decompress by going out to eat with friends, hiking, socializing,” she says. But the isolation and social-distancing measures of the pandemic erased all that. “It felt like a lot of my support system was taken away, that the way I decompress and cope with things was taken away,” Johnson says. “My emotional health started to rapidly deteriorate.”

When Johnson finally got to the point where she felt she was “not capable of showing up”— that her stress and inner turmoil might potentially compromise the care she delivered to patients — she quit the ICU. It was an agonizing choice. “I had to give myself permission to take care of myself,” she says.

“I love my coworkers, and I loved working in the ICU. But this was a weight that I carried for months. I carried it because I knew I was skilled and trained to help during this pandemic. But I also knew that I couldn't be the nurse I needed to be for my patients. And I couldn't keep my emotional health in a good place if I continued to work there. I no longer had the stamina.” Though Johnson left the ICU, she remains at UCLA as a member of the medical-surgical resource team, rotating among the med-surg floors at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center and UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center.

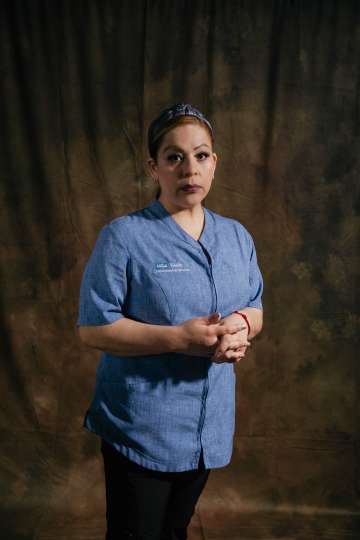

Like Johnson, health care workers at every level experienced heightened anxiety around the novel coronavirus. Many custodial workers were nervous about entering patients’ rooms for fear of the virus. The unremitting awfulness of it all was enough to bring some to tears. “It was very sad to see how the families couldn't be together, talking to their loved ones in the ICU on the iPad,” says senior custodian Beatriz Hernandez, quietly crying as she describes the experience. “Many times, the sick person felt so alone — sad and desperate. I saw so many deaths, including patients who told me they didn’t want to be alone and asked if I could stay with them a moment longer since they couldn’t be close to their families. I tried to be strong and give them support for the brief time I was in their room cleaning,” she says. “I would talk with them. Some of t hem clea rly couldn't speak, but they were looking at me as if to say, ‘Help me.’ I'd tell them everything is going to be OK, don't worry, and I'm cleaning up your room so you can have a speedy recovery. And some did recover, but others died.”

No one was immune to the sadness. Thanh Neville, MD ’05 (RES ’08, FEL ’11), a seasoned critical-care specialist and ICU attending physician, cried many times after finishing her shifts. In one of her many social-media posts over the course of the pandemic, she wrote: “I just left the hospital after a 14-hour day, walked back to my hotel room, and I think I need a long, good cry tonight. I cry for the patient I just lost. I cry for the mother who is not allowed to be at the bedside of her disabled son. I cry for the patient who hasn’t seen her husband for nearly three months. I cry for the newly widowed husband. I think of all the reasons we have to cry right now, and I cry harder.

The pandemic played havoc with the natural instincts of frontline health care professionals who are, as emergencymedicine physician Natasha B. Wheaton, MD, describes, trained “to run toward the fire, toward someone in need.” The tension in the ERs was palpable. “We are trained to adapt and cope and care for patients in the most-difficult situations, but this felt different,” she says. “Not only was there concern for our patients, there also was concern for ourselves and the potential personal risk we would be facing.

Respiratory therapist Garry Knight remembers how “completely scared” he and many of his colleagues were. No matter how urgent a situation was or how strong the desire to “run toward the fire,” he and his coworkers still had to take time to put on full PPE — gowns, appropriate masks, eye protection, double gloves. “You didn’t want a piece of your skin showing, because we didn’t know how you could get this disease,” Knight says.

He was so worried about passing the virus to his fiancé that he developed a meticulous post-shift decontamination routine. Before driving home, he would change out of his work shoes, spray his clothes with Lysol at the front door and head straight into the shower. “I would do my laundry with gloves and a mask on,” he says.

During her fellowship training, Dr. Fazio roared ICU shifts at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center, the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center and Olive View-UCLA Medical Center. Each hospital serves its own communities and mix of patients, and has different levels of resources. Seeing up-close the disparities between the different patient populations contributed to her sense of distress. “As fellows, we were in a unique position to see what was and wasn’t able to be given to a patient based on where they happened to be,” she says. At Olive View, a Los Angeles County facility in Sylmar that is affiliated with UCLA as a teaching center, for example, the supply of ventilators and other critical resources was sometimes stretched thin by the patient load. “To see your decision-making change based on where you were was a very hard struggle,” Dr. Fazio says.

Such experiences also contributed, for many, to erosion of the professional detachment that is necessary for frontline health care workers to focus and do their jobs effectively in moments of urgency. “You try to disconnect when you can, but sometimes you can’t and you feel everything, and it is awful,” Dr. Fazio says. “I am a very resilient person, but there are things that push even the most resilient people to seek help for their emotional well-being.”

Recognizing that one needs help — and then taking the steps to get it — has not had significant standing within the culture of medicine. But asking for help “is a sign of strength,” says Dr. Murthy, the U.S. Surgeon General. “It is a sign that we are human.”

Dr. Neville knew she needed help when her mood tanked and her level of stress soared during the pandemic. “The worst part were the surges,” she says. “That felt very, very different than my normal stresses. And most of that was the pure volume of work and the volume of tragedy.”

Sometimes when she got home at the end of a shift, she didn’t have enough energy left to cry. Even on days off, she couldn’t unwind. “It was hard because I was, like, ‘Why are people happy and doing normal things when there are a whole bunch of people on ventilators?’”

She also couldn’t ignore the physical manifestations of the emotional strain she was experiencing — the exhaustion, insomnia, nightmares when she did finally fall asleep, an inexplicable outbreak of severe hives. Dr. Neville took measures to address her stress and sought relief through acupuncture and breath work at the UCLA Center for EastWest Medicine. And she wrote, sharing her experiences on social media and in editorials. “Writing about how I couldn’t save a patient who had just become engaged and was having a baby allowed me to make the experience of this pandemic much more real for people than just stating the number of deaths. It helps me to know that my words can help people who are not in my shoes understand the gravity and magnitude of this pandemic,” she says.

During the pandemic, additional discussion and drop-in sessions were added to the already robust counseling and crisis-management services that UCLA Health offers its faculty and staff. Such services are necessary to counteract — or at least mitigate — the harm that prolonged stress can inflict. This is particularly true, says Robert Bilder, PhD, professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral science, when traditional coping mechanisms — gathering with friends, traveling, playing sports or taking exercise classes — aren’t available, as has been the case off and on for the past two years.

“People often can handle about one-to-three months of stress pretty well, although it of course depends on the severity of the stressors. What we call acute stress usually lasts less than a month, and our bodies, our brains, our physiology are pretty good at coping for those brief periods of time,” Dr. Bilder says. “But once we get beyond a month of stress, we enter a new phase of chronic stress.” Once a person’s resources for coping have been depleted, “we’re dealing with a whole different spectrum of problems physiologically and psychologically.”

It has been more than two solid years of chronic stress for the nation’s health care workforce. More than 900,000 Americans have died of COVID-19 and in excess of 76 million cases have been diagnosed since the pandemic began in 2020. New variants such as delta and omicron bring on new waves of fear, disease and death. Vaccines became widely available across the country early in 2021, but uptake hasn’t been as broadly embraced as health officials hoped and polarization over the pandemic has worsened. Through it all, health care workers who have remained on the job are still caring for COVID-19 patients while continuing to endure their own physical and mental fatigue.

For Trang Guzze, RN, the pandemic has altered the way she approaches her job as a nurse in the emergency department of UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center. She doesn’t volunteer for extra shifts, as she used to. Instead, she spends time on self-care activities, including exercise and rest. And rather than educating patients, she now, in the superheated political environment that surrounds the disease, often elects to keep quiet. “I signed up to help patients and educate patients, but it’s been so political that I can’t do that,” she says. “My approach now is, ‘I don’t want to fight with you.’”

That, to everyone’s detriment, undermines the traditional role of nurses, says Dr. Grimley, UCLA Health’s nursing chief. Nurses engage in a “social contract” with their patients, she says. They are patient advocates and approach each new en - counter without judgment. But the COVID-19 pandemic has stretched frontline work - ers to their limit. “What we normally do with glee — patient to patient, day to day — is protracted and extremely difficult,” she says. “We’re tired, but we’re resilient. Nurses are fixers and doers, so we’ll come through it.” But in the face of this relentless disease, and too-often the naked hostility of patients and families, “we need space to heal,” Dr. Grimley says. “We need some time. And we need people to be patient and caring with us.”

Having patients second-guess their motivations or in - tentions has been particularly painful for caregivers. “It is important to me that I am viewed as a person who is trying to help, not hurt, people,” Dr. Neville says. “And in this era of misinformation, I can tell you this is a struggle.”

After unrelenting months of combatting the illness on one hand and struggling against tides of misinformation and resistance on the other, many frontline workers caring for unvaccinated patients with COVID-19 feel betrayed by members of the communities they are dedicated to serving. It is a sentiment that has been echoed in numerous articles and opinion pieces. Over the summer, Anita D. Sircar, MD, a UCLA infectious-diseases specialist, wrote in the Los Angeles Times of her “compassion fatigue” toward unvaccinated pa - tients 17 months into the pandemic. “I had cared for hundreds of COVID patients. We all had, without being able to take breaks long enough to help us recover from this unending ordeal,” she wrote. “For those of us who hadn’t left after the hardest year of our professional lives, even hope was now in short supply.”

For Dr. Fazio, it was that sense of waning hope that gave her pause. “It got to the point where I had an elevator pitch for how to talk to a family about their dying loved one,” she says. “And then you realize how crazy that is, and you think about how that’s really the opposite of what humans are designed to do.”

She finally spoke to her supervisors, who insisted she take two weeks off to rest and decompress. Doing so made her feel guilty, knowing her colleagues would have to cover her shifts, “but it was to the point where I was, like, ‘I’ll take the guilt,’ because I was so miserable.”

It is essential that frontline workers like Guzze and others be given the space to talk about the challenges they face, says Robert Cherry, MD, chief medical and quality officer for UCLA Health. “It’s so critical that the staff have their voices heard,” he says. “The key is understanding what their problems are and finding the solutions to help support them.” The silver lining, he adds, is that “during the course of the pandemic, communication between everyone has improved greatly.”

Nearly a year has passed since Dr. Fazio first started to question her professional future. After spending some time in nature, soul-searching about what lay a head, she chose to continue with her fellowship in pulmonary-critical-care medicine. But she also decided to add a research component to her work. Dr. Fazio is now pursuing a PhD in health policy and management “to try to figure out some of those tough questions about how COVID has played out in terms of disparities,” she says. “I think that’s going to be something that will sustain me longer term than being in the ICU all the time.”

Clearly, Dr. Fazio’s life has changed as a consequence of the pandemic. That is true for every health care worker on the frontlines. As Tisha Wang, MD, clinical chief of pulmonary critical care and director of Dr. Fazio’s fellowship program, concludes: “Our souls may never be the same.”