Against all odds, a lifesaving lung transplant

By Mary-Rose Abraham

Photographs by John McCoy

Searing white spotlights beamed onto the roaring crowd as Dead & Company ended their four-hour set on a Saturday night.

Larry “Tony” Arena had already been on his feet for much of the concert. He lined up with 16,000 others to leave The Sphere in Las Vegas. It was nearly midnight and still 84 degrees on The Strip. People packed the air-conditioned pedestrian bridge to The Venetian Hotel.

Tony, 54, increasingly fell behind the exiting crowd. He could only walk about 10 feet before needing to sit down. Even the portable oxygen machine slung across his shoulder wasn’t helping.

“I couldn’t breathe at all,” Tony recalls.

Foot traffic in the long passageway thinned out; soon, it was just Tony and his college buddy Mike. What should have been a brisk, 10-minute walk to the hotel took them over an hour.

After Tony and his wife, Kamren Arena, drove back to their San Diego-area home, he twice coughed up blood. They went to the local hospital, where over the next several days, his condition worsened.

On July 3, 2024, an ambulance transported Tony up to Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center where he was admitted in respiratory failure and approved for a double lung transplant. The wait for the organs needed to save his life had begun.

Since June 1990, more than 1,780 patients have received a lung transplant at UCLA Health, placing it among the top 10 centers nationwide. And despite many high-risk cases, patients overall go home far quicker: a median of 13 days after transplant, compared with 19 days nationally.

But these numbers only begin to capture the scope of the transplant program at UCLA Health, which leads the nation with 24,000 solid-organ transplants since its beginnings.

Clinician–scientists at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, supported by research dollars from the National Institutes of Health, have transformed lung transplantation worldwide.

A novel device that began as a paper napkin sketch has radically improved ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation), technology that keeps patients alive while on the transplant waitlist.

In addition, research breakthroughs have expanded the pool of viable donor organs. UCLA Health led the largest clinical trial in the study of ex vivo lung perfusion, the platform that allows organs to live outside the body longer.

“The UCLA team are not the people who come in, do their work and go home,” says Abbas Ardehali, MD, director of the UCLA Health Heart and Lung Transplant Program. “We continue to ask questions. Why? What? How can we do better?

“This is what we do every day: not only charting new territories but offering lifesaving therapy.”

In the following days, the transplant team would need to call on that skill and willpower to heal Tony. Like many other patients needing new lungs, his challenging health issues complicated an already fraught procedure. UCLA Health was his last resort.

Tony was admitted to 4ICU, the medical intensive care unit on the 4th floor of the hospital in Westwood. It wasn’t the first time he was critically ill.

In late summer 2012, the general contractor spent a day pulling weeds at a worksite with his son. Two days later, he couldn’t lift his right arm. When he tried, the pain was so intense that he cried in the shower.

An MRI and a consultation with a hematologist followed. Tony was diagnosed with an aggressive form of the blood cancer Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. He and Kamren had married just six weeks earlier.

The treatment was intense: six months of chemotherapy and a stem cell transplant from his sister, who was fortunately a match. In less than a year, Tony and Kamren were able to travel again.

His cancer was cured and all seemed well. But around 2018, Tony developed a persistent, dry cough so intense, it would double him over. He was so fatigued, he had to close his contracting business.

A pulmonologist determined that Tony’s stem cell transplant had resulted in graft-versus-host disease (GvHD). The transplanted cells were attacking his body, and significantly scarring his lungs.

Tony would likely need a lung transplant, but surgeons at his local medical center weren’t comfortable taking him on because of his health complications. He was referred to UCLA Health, which routinely accepts patients who are deemed too sick or too elderly for a lung transplant and turned down by other medical centers.

Dr. Ardehali explains that surgery on a patient with GvHD presents “a challenge because of their overall state of immunosuppression” and risk for infections. In his 28 years with UCLA Health, he has performed lung transplants on at least a dozen patients with the unusual condition.

“It’s because of the expertise that we have — the ICU, the critical care team — the whole package comes together to provide care for patients who pose significant challenges.”

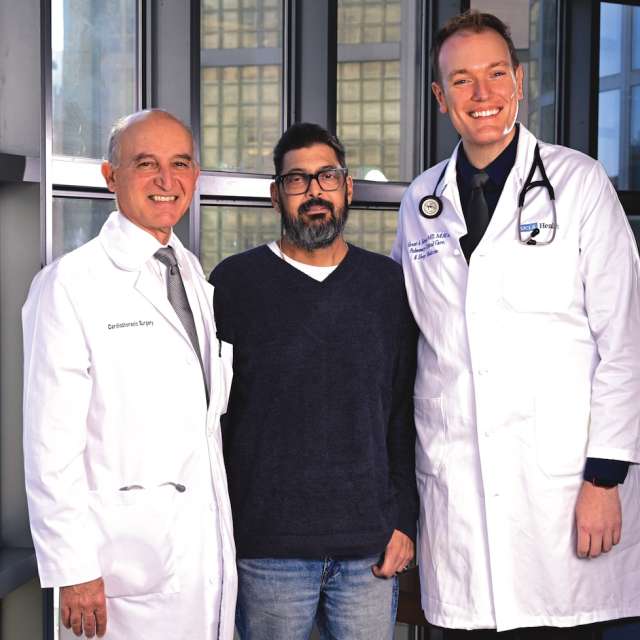

A team of specialists gathered for their weekly Thursday morning meeting to consider whether Tony and other patients should be added to the national transplant waiting list. On the call was Tony’s pulmonologist, Grant Turner, MD, MHA.

The flare-ups of Tony’s lung issues were unpredictable. Dr. Turner recalls that when he listened through the stethoscope, it “sounded like ripping the Velcro on a pair of shoes. I heard crackles all throughout his lungs.”

Tony was still healthy enough then that he didn’t need an immediate transplant. But Dr. Turner had him undergo all the necessary tests in case his condition deteriorated: bloodwork, ultrasounds, screenings for pulmonary hypertension and coronary artery disease.

Next were appointments with an infectious disease physician, cardiologist, psychiatrist, nephrologist, nutritionist, dentist, social worker and financial counselor. Completing them all took three months.

It was many of these same specialists who discussed Tony’s case during that morning meeting, more than a year after he was referred to UCLA Health. Dr. Turner presented a detailed overview of his condition. Then Dr. Ardehali called on each person to provide an assessment.

Incorporating everyone’s perspective helps to strike a delicate balance.

“Our goal is to make sure that every patient has the best chance of survival and getting through the surgery,” says Dr. Ardehali, also a professor of surgery and medicine in the medical school.

“But we are also cognizant that we are entrusted with a valuable resource: the scarce donor organs. If we give one to a patient who doesn’t survive, it means that it was taken away from somebody else.”

By the end of the meeting, Tony had been added to the waiting list for a donor lung.

“Organ transplantation is one of the miracles of modern medicine. It's so gratifying for the team to see how a procedure so dramatically impacts one's life.”

Matching donors to recipients is a complex process. Dr. Ardehali explained that among the parameters are blood type and body size.

As Tony saw it, “There are benefits to being average height. You have a wider selection.”

For the most part, though, “How sick you are determines when you are matched with a donor,” Dr. Ardehali says.

But even with a match, only visualization — a careful examination of the organ — determines if the transplant proceeds.

A little more than two weeks after Tony was admitted, a donor lung was found. He was prepped for surgery.

Dr. Ardehali’s colleagues on the transplant team went to the hospital where the donor had been brought.

The lungs were the second organ to be removed from the donor’s body (after the heart). It was a deep red, unlike a pinkish healthy lung, and filled with fluids, a sign of pneumonia throughout. It was decided not to transplant.

Tony was more than disheartened as he continued to wait in the ICU.

“I remember being scared,” says Tony. “I remember praying a lot to God at night, asking him to watch over me.”

Having Kamren and his 83-year-old father, Dominick Arena, by his side comforted him, as did the bond he formed with a 4ICU nurse, Mark Ramos, RN, CCRN. They talked about everything from sourdough bread to family to religion.

But the wait was “torture,” as Kamren describes it.

“You stare at every doctor, every time they walk by, because you think: Are they going to come in and give you an offer?”

Five days later, Tony’s blood oxygen levels were critically low. He was moved up to 7ICU, the cardiothoracic intensive care unit, and placed on ECMO.

A catheter on the right side of his neck branched into his heart and lungs, efficiently delivering oxygenated blood. That kept him alive.

Even with tubes running throughout his body, Tony was able to talk and frequently walked around the ICU. That kept him eligible for a transplant.

“If you’re not able to be active, then it’s unlikely you’ll have a good outcome afterwards, even if the lung itself is great,” Dr. Turner says.

Two days after he went on ECMO, Tony was once more matched with a donor lung.

He was again prepped for surgery. Kamren and Dominick sat outside in a courtyard, silently watching as helicopters landed on the roof of the hospital, wondering if one of them was delivering the lifesaving organ.

In the operating room, Dr. Ardehali opened Tony’s chest like a clamshell. His fibrotic lungs were stiff and barely able to expand, pooled blood coloring them a dark red.

Five days later, Tony’s blood oxygen levels were critically low. He was moved up to 7ICU, the cardiothoracic intensive care unit, and placed on ECMO.

A catheter on the right side of his neck branched into his heart and lungs, efficiently delivering oxygenated blood. That kept him alive.

Even with tubes running throughout his body, Tony was able to talk and frequently walked around the ICU. That kept him eligible for a transplant.

“If you’re not able to be active, then it’s unlikely you’ll have a good outcome afterwards, even if the lung itself is great,” Dr. Turner says.

Two days after he went on ECMO, Tony was once more matched with a donor lung.

He was again prepped for surgery. Kamren and Dominick sat outside in a courtyard, silently watching as helicopters landed on the roof of the hospital, wondering if one of them was delivering the lifesaving organ.

In the operating room, Dr. Ardehali opened Tony’s chest like a clamshell. His fibrotic lungs were stiff and barely able to expand, pooled blood coloring them a dark red.

Dr. Ardehali removed Tony’s lungs, slipped in the inflated donor lungs and connected airways and vessels. The new lungs began to expand and collapse and took on a pinkish color as blood began to flow.

Dr. Ardehali also repaired a hole in Tony’s heart. As a cardiothoracic surgeon, he was able to operate on the heart as well during the transplant procedure.

The surgery that had been estimated to take six hours was complete in just four and a half. Dr. Ardehali came out to the waiting room and reassured Kamren and Dominick that the surgery went well. They both started crying and hugging him.

“Nowhere in medicine can you do something that has this much of an impact in such a short period of time on an individual’s life,” says Dr. Ardehali. “Organ transplantation is one of the miracles of modern medicine. It’s so gratifying for the team to see how a procedure so dramatically impacts one’s life.”

He is quick to point out the true heroes in transplantation: the donor and the donor’s family.

“The courage to donate organs so they can save others is a testament to their resilience,” Dr. Ardehali says. “At a time of tragedy, they do something good for the community and society as a whole.”

In the ICU, Dr. Turner has seen the journey of a donor organ “from the other side of things,” he says.

“The families are bereft and beside themselves from some horrible, traumatic accident — but still give the gift of life to other people.”

Though Tony doesn’t remember much while on ECMO, he does have a singular, strong memory: A vision of blue angel wings bearing a message that Kamren and Dominick were the hands that would help him heal.

That vision came true as they stayed with him around the clock for the critical first three months post-transplant.

Tony had to re-learn two basic reflexes: breathing and coughing. Both were painful because of the incision that was healing across his chest.

“As weird as it sounds, I went from ‘couldn’t stop coughing’ to ‘couldn’t cough at all’,” Tony says.

Dr. Turner explained that Tony’s intercostal muscles between each of his ribs had atrophied and he needed to re-expand them with deep breathing. The nerves that would normally prompt him to cough and clear his airway had been permanently severed.

“We force them to cough a lot,” says Dr. Turner, also an assistant clinical professor of medicine in the medical school. “They don’t really feel like it, but that mucus is sitting down there, and it has to get out one way or the other.”

Nurses gave Tony a very firm teddy bear to hug. It supported the incision to lessen the pain. It also pushed his diaphragm in, forcing air out and helping Tony cough.

“God, I hated the bear,” he recalls.

Tony was discharged from the hospital just 12 days post-transplant. Kamren rented a nearby apartment so they could meet regularly with Dr. Turner for the next two months. In September, they finally returned home.

On Tony’s 55th birthday — the first one after transplant — they put in an offer on a new home by the sea. Tony was able to enjoy “simple things like walking on the beach without needing oxygen,” he says.

“Being able to breathe and have a conversation without coughing is life-changing.”

A little more than a year after transplant, Tony and Kamren drove up to Westwood for his periodic tests and consultation with Dr. Turner.

The exam room in the pulmonology clinic was chilly, so Marisol Oreas, LVN, brought Tony a blanket and heat packs. She clamped an oximeter to his index finger. A few seconds later, the monitor read 100 — his blood oxygen level was at its peak.

Dr. Turner joined them. After spending so much time together before, during and after transplant, there was a close bond and an easy camaraderie. Kamren first wanted to know if it was safe to go camping.

“Being able to breathe and have a conversation without coughing is life-changing”

“Maybe you should try glamping instead,” joked Dr. Turner.

He checked Tony’s lungs. No wheezing or crackles to be heard.

“Sounds great!” Dr. Turner says, removing his stethoscope.

Tony’s main issue now is a common one: side effects from the medications to keep the donor lung from being rejected. And because they lowered his immunity, he was also battling a viral infection. Dr. Turner adjusted the dosage on the current drug and introduced a new one.

He encouraged Tony to work out at the gym — off-peak hours to reduce the risk of infection — and planned to meet him again in another six weeks.

As they got ready to head back to San Diego, Kamren reflected on Tony’s challenging health journey which had brought them to UCLA Health.

“The transplant team is super passionate,” she said. “This is their thing, and it makes you feel like they care so much about you. It’s not just one doctor; it’s the whole team. They all know you. And I think that’s so special.”

Learn more about the UCLA Health Heart and Lung Transplant Program.

Featured In

Related Content

Articles:

Services:

Physicians

A new home for transplant medicine innovation

UCLA Health is an undisputed leader in the field of solid organ transplantation, a lifesaving procedure for patients with end-stage organ failure. For countless people, a transplant is the only option for survival. Despite advancements in medical science, there remains a significant gap between the number of patients needing transplants and the availability of donor organs.

To help bridge this gap, UCLA Health will establish the UCLA Organ Transplant Institute, a state-of-the-art center dedicated to advancing transplantation science, patient care and education. Set to open in the coming years, the Institute will provide comprehensive transplant services, foster innovative research and offer extensive education and training programs.