Nothing could have prepared Gerald Lipshutz, MD, for what he experienced at a small patient-physician symposium in 2022 in Utah.

Amid technical talks and clinical data presentations, parents shared raw accounts of life with creatine transporter deficiency — a condition that left their children unable to speak, prone to seizures and far behind their peers developmentally. Their rare genetic disorder starves the brain of a vital energy source and robs families of a typical childhood. And there was no treatment.

“It sounds corny, I know,” said Dr. Lipshutz, a professor of surgery and molecular and medical pharmacology and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA. “But when you meet these families, you either walk away sad, or you stay and try to help.”

He stayed.

Dr. Lipshutz’s journey into the world of rare diseases began not in a lab, but in the operating room. As a surgical transplant fellow at UC San Francisco, he encountered patients undergoing liver transplants for single-enzyme deficiencies.

“I remember thinking there has to be a better way,” he said. “We’re transplanting entire organs because of one abnormal enzyme.”

His instinct to find a molecular fix instead of a surgical one eventually led him into the emerging field of gene therapy, where for years, he focused on developing therapies for liver and metabolic disorders.

But moved by the parents’ resilience and frustrated by the scientific inertia surrounding CTD, he knew he had to add the brain disorder to his research program.

Now, with a grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, or CIRM, Dr. Lipshutz and his team are working to develop a one-time gene therapy for CTD. While still in early development, he believes this approach has the potential to transform the lives of affected children and offer a template for treating other rare diseases.

What happens when the brain runs out of fuel?

Estimated to affect approximately 1 in 225,000 individuals worldwide, CTD is an X-linked disorder that is commonly associated with global developmental delay, in which children lag significantly behind their peers in speech, motor skills and cognitive abilities.

The condition is caused by mutations in the SLC6A8 gene, which encodes the creatine transporter responsible for ferrying creatine across the blood-brain barrier and into cells. Without this transporter, creatine — the molecule that helps regenerate adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, the body’s energy currency — can’t reach the brain.

While most of the body’s energy comes from glucose, organs with high-energy demands like the brain, heart and muscles require creatine as a critical second fuel source to function normally.

The symptoms of CTD are often severe: limited or absent speech, seizures, intellectual disability and in some cases, behavioral challenges that impact daily life. Diagnosis for the disorder is often delayed due to its rarity and lack of awareness among the medical community. CTD isn’t on newborn screening panels, and many parents spend years searching for answers.

A promising strategy for gene delivery

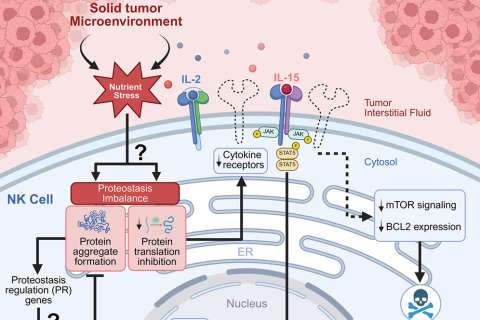

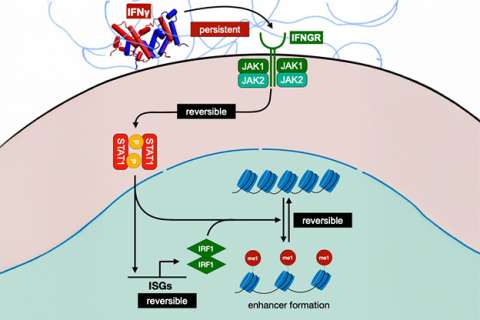

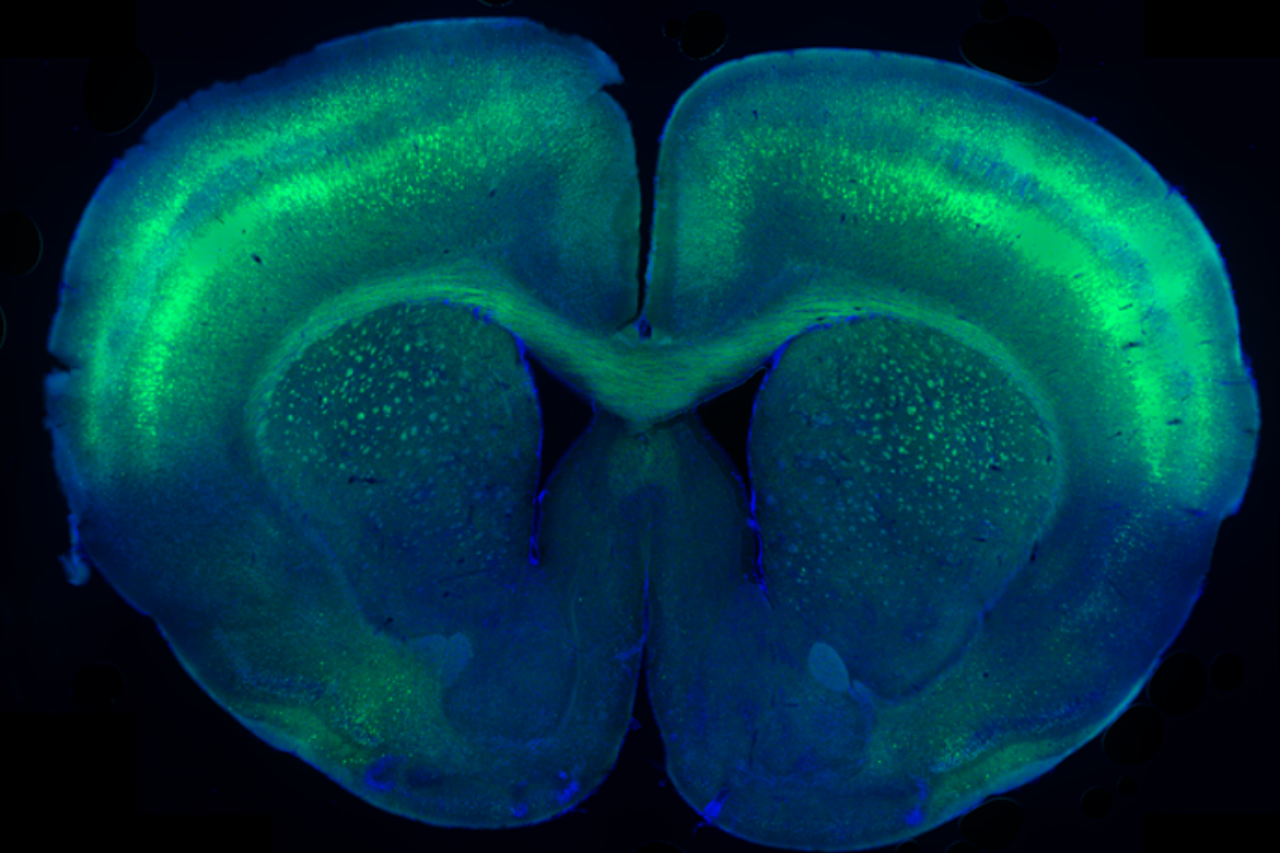

Only a handful of labs worldwide are studying CTD, and none has brought a therapy to clinical trials. While some have attempted to deliver gene therapies for this condition directly into the brain’s cerebrospinal fluid, Dr. Lipshutz and his team are targeting the bloodstream. They are using a modified viral vector that can cross the blood-brain barrier and deliver a healthy copy of the SLC6A8 gene to cells throughout the brain.

The results have been striking in preclinical studies. Mouse models of the disorder treated with a single, moderate dose of the gene therapy showed not only widespread, restored levels of creatine in the brain, but also changes and improvements in behavioral activity.

There are still technological hurdles ahead — most notably sourcing and implementing a viral vector that can cross the blood-brain barrier in humans — and funding for rare disease therapies remains a challenge.

But Dr. Lipshutz believes if they can overcome these obstacles, the therapy could be transformative for children who receive it early, ideally before the most severe symptoms emerge.

Advocacy, awareness and a viral victory

Increased awareness is critical to securing additional funding for this research — and that awareness is growing, thanks to people like Jeffrey Randall Allen, who recently won YouTube celebrity MrBeast’s competition show “Beast Games” on Amazon Prime Video and dedicated the victory to his son, Lucas, who lives with CTD.

Lucas was diagnosed at age 2 after what Allen describes as a long and frustrating “diagnostic odyssey” filled with months of worrying why he was missing developmental milestones. When Allen and his wife, Jen, finally learned what was afflicting their son, they were overcome with two realizations: they had an answer, but no solution.

“That’s when we realized our life wasn’t about us anymore,” Allen said. “It was about helping him and kids like him. And that gave us perspective and gratitude.”

Lucas, who turns 8 years old on July 18, needs help with everyday tasks, including going to the bathroom. He faces severe speech challenges that affect his ability to communicate his needs, desires, pains and joys to those around him. Without any treatment or management options, the only strategy available to the Allen family is dividing and conquering his needs — and balancing them against those of his older brother, Jack.

The family’s daily struggles fuel Allen’s advocacy, which began long before his Beast Games tribute. He’s served as vice chair of the Association for Creatine Deficiencies — the very organization that hosted the eye-opening patient-physician symposium Dr. Lipshutz attended — since 2020.

His recent viral victory was a springboard for another awareness-raising effort: This past March, he walked 365 miles across California carrying a backpack with the weight of his son — a symbolic tribute to the 365 days each year Lucas carries the burden of his condition.

“Since the show aired, I’ve heard from people all over the world — from Argentina to academic labs — who now know about CTD and want to help,” he said. “The Beast effect is real.”

A critical turning point for hope

Dr. Lipshutz emphasizes that while his team has made important progress, significant preclinical work remains — and new funding will be essential to keep it moving forward. The next challenge is translating success in mice to humans, and overcoming a critical hurdle: delivering the therapy across the human blood-brain barrier.

The viral vector strain used in mice doesn’t yet work in people. To address that, Dr. Lipshutz is exploring partnerships with groups developing delivery tools that can safely and effectively reach the human brain — a breakthrough that could unlock treatments for a host of neurological diseases.

“We don’t have access to that technology yet,” he said. “But if it works, it could change everything.”

Securing new funding will be key to adapting the therapy for human use and taking the next steps toward clinical trials.

“We’re being cautious,” Dr. Lipshutz added. “There are still critical steps ahead, but we’re doing everything we can to get there.”

‘Our goal is bigger than Lucas’

For parents like Allen, the promise that there could one day be a therapy, even an experimental one, means everything — but he knows it will be a steep uphill climb.

“Our goal is bigger than Lucas,” he said. “It’s about the kids like Lucas, and those who haven’t even been born yet. If they can get therapy at birth, we’ve essentially eradicated this condition.”

Dr. Lipshutz shares that hope. For children diagnosed early, gene therapy could prevent symptoms from ever taking hold. For others already living with CTD, it could hopefully improve quality of life — not only for them, but for their families, whose experiences are never far from his mind.

“He’s not just looking at things in a petri dish or under a microscope in a lab,” Allen said of Dr. Lipshutz. “He’s meeting kids like mine and etching their faces and names into his work.”

Someday, Allen imagines a moment when a therapy comes to fruition and Lucas, in his own way, can tell him: We did it, Dad.

“That’s going to be our legacy,” Allen said.