It's widely known that there is a connection between autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and epilepsy, but what the precise nature of that relationship is “is the million-dollar question,” says Hiroki Nariai, MD, PhD, MS, assistant professor of pediatrics, division of pediatric neurology, and medical director of the pediatric epilepsy surgery program at UCLA.

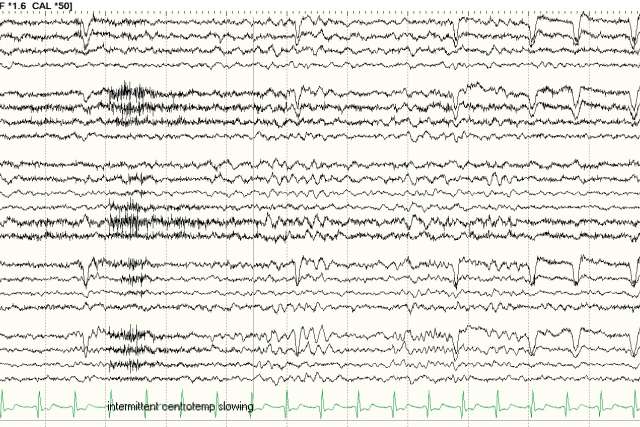

Dr. Nariai, who specializes in pediatric epilepsy, is lead author of a UCLA published study which examined data from electroencephalograms (EEGs) conducted on children with ASD. In looking at 15 years' worth of EEGs, researchers may have found a possible way to predict epilepsy risk.

Dr. Nariai offers insights for parents and clinicians in the following Q&A.

Q: What is the connection between autism and epilepsy?

Dr. Nariai: The short answer is we don’t have a comprehensive explanation. The exact underlying mechanisms for this connection are still being studied. However, about 20-40% of children with autism eventually develop epilepsy. That’s a BIG number, compared to 1% of the general population.

On the flip side, children with epilepsy, especially the severe form, have high association with autism. Both conditions share a common brain pathophysiology. Clinicians intuitively know there’s a reciprocal relationship; they often deal with those conditions within the same individual.

Q: Why did the study focus on EEGs?

Dr. Nariai: Kids with autism often get EEGs because of abnormal behaviors. A child may not respond to their name, lose language skills, exhibit random body jerking — many reasons. Some 25-80% of these children have abnormal EEGs. (Many small studies report the numbers, so there is variability.) Is it just a coincidence? Does it give us any clues? Clinicians need to know how to interpret the EGG results; that’s the whole point.

Q: How was the study performed?

Dr. Nariai: To clarify, we didn’t design and start this study 15 years ago. We examined a database of EEGs conducted on kids with autism over 15 years. Approximately 150 kids in the cohort had gotten long (12-24 hours-duration) EEGs due to concern they might start having seizures. Almost none of them had seizures at that time. We tracked when those children developed epilepsy within that 15-year period.

Q: What, specifically, did you find?

Dr. Nariai: We looked at interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs), commonly called spikes — excitations of the neurons, a precursor of seizures. It’s intuitive to say those spikes indicate the child may have a higher risk of developing epilepsy; that’s one finding.

The other finding was unexpected. We expect to see a certain frequency of EEG background activity in each child, depending on their age. In children with autism, we saw a lot of slow wave activity. Even pediatric neurologists and epileptologists have a hard time interpreting slow waves.

This data is intriguing because we found the presence of EEG slowing ALSO predicts future development of epilepsy. We didn’t think that would be the case, but data showed exactly that. This likely signifies an underlying pathology, a brain network issue.

Q: What percentage of children with EEG spikes or slowing develop epilepsy?

Dr. Nariai: That’s a very practical question; clinicians and families need answers. We reported both positive and negative predictive values in the study. Of patients with EEG spikes or slowing, the positive predictive value tells us about 60% will develop epilepsy.

The negative predictive value is also important. When a long EEG was completely clear, the negative predictive value was more than 80% that the patient would not develop epilepsy for a while. Of children with no spikes or slowing, about 90% did not have seizures five years after EEG testing.

Q: Who can use this information, and how?

Dr. Nariai: In addition to pediatric neurologists and epileptologists, pediatricians and primary care physicians need to understand the value of the EEG as a diagnostic tool and how to explain findings to families.

If a child’s EEG is abnormal, we can tell parents their child has a high risk of developing epilepsy down the road. That’s very useful information. We can educate them about seizures and epilepsy. We can help them feel prepared.

And, if the EEG is clear, we can bring parents’ anxiety levels down; they can relax a little bit.

Q: Should EEGs be done regularly to monitor epilepsy risk?

Dr. Nariai: No. The American Academy of Pediatrics doesn’t recommend routine EEG testing on children with autism without a clear reason. Kids with ASD have sensory issues; many need sedation at a hospital to get an EEG done. Some of these children get upset, pull the sensors off.

And then the cost is hard to ignore. It’s very expensive in the United States. If we could prevent epilepsy from occurring, that would be justification. But we’re not there yet.

Q: What do you consider the big takeaway from the study?

Dr. Nariai: In the past, EEG reports have been very, very confusing. Now we have information on how to interpret them. This study, based on big clinical data, gives some important guidance. It helps us to prepare and educate families.

And this study opens the door to more research which we hope eventually will lead to an intervention to prevent epilepsy. This is a new starting point that we did not have before.