In her first year at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Katharina “Kat” Schmolly, MD, heard an old saying: “When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses, not zebras.”

The phrase is a caution for physicians to prioritize likely causes rather than uncommon diagnoses. As an undergraduate student of equine science and a former horse trainer, Dr. Schmolly was on board.

But she began to reconsider during a hepatology lecture by Simon W. Beaven, MD, PhD. At his clinic in the Pfleger Liver Institute, Dr. Beaven treats patients with acute hepatic porphyria (AHP), a family of rare genetic diseases. Symptoms affect mostly women, often coinciding with the menstrual cycle, with severe, sometimes life-threatening, attacks of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, limb weakness and anxiety.

“Women unfortunately get dismissed when they go to the emergency department over and over again for these complaints,” said Dr. Schmolly. “Because it looks like it's menstrual pain, but actually, it could be a true liver disease.”

The unfairness of it inspired her to found zebraMD, which uses artificial intelligence to help diagnose and manage rare diseases. A predictive algorithm combs through electronic health records to identify disease patterns and flag patients who may be at risk so physicians can further test and diagnose – highlighting the rare “zebras” over commonly known “horses.”

“The diagnostic delay is roughly 10 to 15 years for these diseases because physicians don't see them very often,” said Dr. Schmolly. “And while waiting for diagnosis, the disease can progress and cause irreversible damage. So, our goal is to diagnose patients earlier and manage their disease appropriately.”

Not so rare

By definition, a rare disease affects fewer than 200,000 people. But more than 10,000 known rare diseases cumulatively affect 1 in 10 Americans, the same prevalence as diabetes. A few, including variants of multiple sclerosis, are well known, but the majority – bartonellosis, maple syrup urine disease and visual snow syndrome – are not.

AHP affects 1 in 100,000 people. The FDA approved givosiran in 2019 as a prophylactic treatment – but it takes an average of 15 years for diagnosis. To speed things up, the drug’s manufacturer, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, approached the UCSF Porphyria Center about developing an algorithm to identify possible patients.

Vivek Rudrapatna, MD, PhD, is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology at UCSF and director of The Real-World Evidence Lab, which applies data science techniques to electronic health records.

“Given that it's a rare disease, we knew that it was going to be difficult or impossible to run this as a single center endeavor,” Dr. Rudrapatna said.

When Dr. Schmolly approached Dr. Beaven about her interest in rare diseases, he connected her with Dr. Rudrapatna. Building off of his clinical data science background and Dr. Schmolly’s past experience working on a diagnostic algorithm at Medtronic, the pair co-invented Project Zebra’s predictive algorithm to identify suspected porphyria patients based on de-identified patient records from UCSF and UCLA.

The first challenge for the algorithm: messy data.

Patient records comprise structured data, including vital signs, lab results and demographic information, and unstructured elements such as physicians’ notes. Algorithms struggle with the latter.

The researchers massaged the data to convert unstructured clinical data to tightly organized, curated information the algorithm could use – a “Herculean challenge that was 90 percent of the effort for this study,” Dr. Rudrapatna said. “They're not going to learn much without some elbow grease.”

Another challenge was masking data points that would allow the algorithm to “cheat” in making a disease prediction – essentially, blinding the algorithm before a clinical suspicion of disease exists.

For example, “a clinician refers a patient to [a porphyria specialist],” said Dr. Rudrapatna. “And then there's a referral order that pops up as structured data. The algorithm will see the referral and predict porphyria.

“If that's already happened, the algorithm is never going to learn to identify these patients earlier. What we want are algorithms that can really discover these patients way before clinicians are consciously thinking about it.”

So what clues to AHP is the algorithm looking for?

To help it learn, Drs. Rudrapatna and Schmolly provided their model with three resources. The first was expert knowledge from Bruce Wang, MD, director of the UCSF Porphyria Center, who shared information on symptoms and symptom constellations. Second was access to a rare and genetic disease database from the National Institutes of Health which included signs, symptoms and presentation patterns for porphyria patients.

Third was allowing the algorithm to sift through the data and discover signals on its own. This is especially important, Dr. Rudrapatna said, because rare diseases can be misdiagnosed so often.

“If you're a porphyria expert, you're thinking primarily about the signs and symptoms,” he said. “But you might not be thinking about all the possible misdiagnoses these patients could have before they get diagnosed. An algorithm could find the tests that they're getting [while] moving down the wrong track. What are the erroneous therapies that they’re receiving because they're misdiagnosed? Who are the providers they're seeing?”

In their study published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, the researchers found the algorithm predicted patients would be referred for AHP testing by a range of 89 to 93 percent accuracy. And when it came to predicting who tested positive for the disease, the algorithm recognized 71 percent of patients earlier than their actual diagnosis, corresponding to an average time saved of 1.2 years.

Privacy and permissions

For any machine learning model, accessing patient data can often mean a lengthy approvals process. And since algorithms learn and perform better given massive datasets, health care records from a range of institutions would be ideal, though permissions would be a barrier.

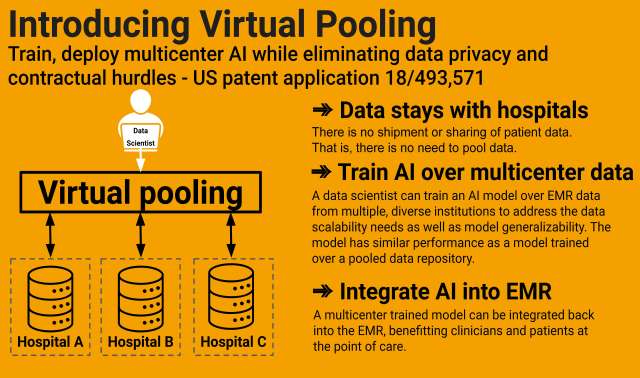

To get around this, zebraMD uses Virtual Pooling, a patented technology developed by collaborator Trinabh Gupta, PhD, an assistant professor in the department of computer science at UC Santa Barbara. Virtual Pooling allows algorithms to learn from data without their explicit transfer.

“Owners of clinical data can maintain local control and security and privacy,” said Dr. Rudrapatna, “but at the same time, allow machine learning models to learn from that collected experience, and then leave with those insights without leaving with the data itself.”

An important part of training the AHP algorithm is validation by a specialist physician to ensure that its results are medically sound. Dr. Schmolly said the goal this year is to validate up to 350 diseases with an accuracy of at least 85 percent.

Project Zebra is currently training its algorithm to predict cerebral aneurysms, a condition in which a weakened blood vessel in the brain balloons out or expands.

Aneurysms are fairly common: about 1 in 50 to 1 in 100 Americans have an unruptured brain aneurysm. But rupture is a rare condition that affects about 30,000 people in the U.S. every year, with many fatalities. Diagnosing a brain aneurysm before it ruptures is key.

Advising the Project Zebra team as it develops a predictive algorithm for cerebral aneurysms is Geoffrey Colby, MD, PhD, a professor of neurosurgery and radiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the director of cerebrovascular neurosurgery at UCLA Health.

If the algorithm flagged a patient, Dr. Colby would order imaging studies to carefully look at the blood vessels, “find people that have aneurysms and catch them before they have a problem,” he said. “But we don't want the algorithm to identify a lot of false negatives. We don't want to incorrectly alarm lots of people.

“My hope for this project is about identifying the people who need help and reducing the number of people who undergo a life-threatening event every year.”

An eye on the future

Kristen Cardon, a software engineering intern and doctoral candidate in UCLA’s English department, is working on a new web app for Project Zebra. Her cousin has a rare condition called Williams syndrome, characterized by cardiovascular disease and delays in cognitive development.

“At a time that could be scary, our app is just making information accessible, easy and functional,” Cardon said. “I see it as a part of mental health justice as well as health justice more generally.”

In Winter 2024, zebraMD will test its algorithms in the real world by embedding into electronic health records systems at Ronald Reagan Medical Center at UCLA, Olive-View UCLA Medical Center, UCSF and Dartmouth Health.

“The more patients we can diagnose, the more we can monitor over time, learn what works and what doesn't work. We can create precision medicine approaches for these rare diseases,” said Dr. Schmolly, who will continue to lead the team during her internal medicine residency on a physician-scientist track at Dartmouth Health. “Many of them don't have any treatments yet. So hopefully, we can find new options for them.

“I hope that at some point, this is a standard feature of any electronic health records system.”