A child’s spine curved by scoliosis. The forearm of a woman bitten by a dog.

These are not photos or preserved specimens, but life-size models of a dull white plastic. Created by a 3D printer, the objects replicate real-life patient injuries and conditions.

“What makes 3D printing interesting for medicine is that it is one of the few technologies that allows you to make one of anything,” said Darryl Hwang, PhD, clinical imaging IT specialist in the department of radiology at UCLA Health.

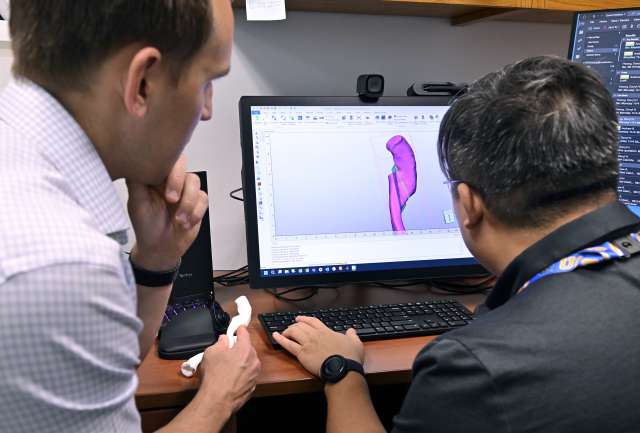

Dr. Hwang manages the Department of Radiological Sciences 3D Printing and Media Center, which works with providers and researchers across the health system.

Three-dimensional models help patients better understand what’s going on in their bodies. And they guide surgeons with a visual and tactile aid before they step into the operating room.

3D-printed models of patients’ hearts have already been in use by UCLA Health cardiologists for more than five years.

The technology has expanded to orthopedics. An early adopter is Andrew Jensen, MD, MBE, who specializes in shoulder and elbow reconstructive surgery.

He uses models to practice procedures, thereby improving accuracy and cutting down on time in surgery.

“Instead of going in blind, practicing gives me the confidence to follow the steps – similar to a recipe in baking or instructions for assembling furniture,” said Dr. Jensen, an assistant professor of orthopedic surgery at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

From imaging to model

3D printing began in the 1980s and has progressed rapidly from solely industrial use to affordable home printers.

In health systems, 3D printing provides personalized medicine tailored to an individual patient.

The only limitations, Dr. Hwang noted, are the print size and the availability of high-resolution, three-dimensional images.

Advancing imaging, such as CT and MRI – “any 3D modality that preserves the shape and doesn't have too much distortion” – serve as the templates for 3D printers.

Once the image is captured, a Photoshop-like program segments the image to remove extraneous body parts and tissues, which helps produce a quality model.

Orthopedics is particularly suited because “CT loves bone and you can get very good, high-resolution images,” according to Dr. Hwang.

And since many aspects of the body are symmetrical, the CT image can be flipped to generate a model of the other side of the body. That allows the surgeon to match the two sides – for example reconstructing a left clavicle to mirror the right.

The 3D printers used in the lab either melt plastic filament to extrude a 3D shape or expose ultraviolet light onto a liquid resin to harden it into a solid.

For most uses, the plastic filament is an inexpensive PETG plastic – the same base material as in water bottles.

The model that emerges is durable and feels “similar in texture, but definitely lighter than bone,” said Dr. Jensen.

“Usually there are muscles and blood vessels and nerves, and it's in the body, so it's a little bizarre to just hold a bone,” he said. “But overall, visually it looks super realistic. It's really incredible.”

Pre-op practice

It takes a few weeks for the models to be created, so they are usually used for orthopedics procedures planned well in advance.

Most of these procedures are revision surgeries, in which a fracture hasn't healed or has healed incorrectly.

Before 3D printing, Dr. Jensen had few options to do a practice run of a procedure. One was to use a generic model of a bone.

But now he can take a 3D print customized to an individual patient into a lab, make the appropriate cuts and work with replica medical implants to simulate the entire procedure. This helps him cut down on surgery time and achieve greater precision.

That’s especially important for cases in which a few degrees’ difference in cutting the bone would result in “drastically changing whether a clavicle was pointing backwards or forwards,” he remarked.

“If you don't go through this process in these unique cases, you're just going in blind.”

Future outlook

The Media Center’s 3D printers are currently located in a basement lab. But in the future, they may be sitting alongside other surgical tools in the operating room.

“Someday it'd be really cool if I could get a quick CT scan and then we could have a 3D printer that prints out the implants right there during surgery,” Dr. Jensen said.

Dr. Hwang also foresees the expansion of 3D printing. For example, a patient with a broken arm may get a CT in the emergency room, and a little later in the visit, have a custom cast printed.

“3D printing is just a tool,” he said. “How we want to use that tool just takes creativity and willingness to experiment and see what works out.”