Working with the UCLA Health Homeless Healthcare Collaborative during graduate school changed Zoe McFall’s life.

As part of UCLA’s nurse practitioner master’s program, McFall, FNP-BC, was assigned to a 10-week rotation in 2022 with the mobile unit that provides critical health services to people experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County.

McFall was already a nurse with UCLA Health, but her experiences with the Homeless Healthcare Collaborative broadened her view – and opened her heart – to the breadth of what’s possible in community health care.

“It’s one of the best things that ever happened to me,” says McFall, now a board-certified family nurse practitioner with the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. “My rotation with the Homeless Healthcare Collaborative honestly changed my perspective on health care. It laid a foundation for the care I will provide as a medical provider.”

Eye-opening experience

Students studying to become family nurse practitioners at the UCLA Health School of Nursing typically participate in seven field rotations during the two-year program. These applied-practice experiences might be in pediatrics, the emergency department, a neighborhood clinic or other medical setting.

Not every graduate nursing student gets to train with the Homeless Healthcare Collaborative, which operates five vans and can only accommodate two nursing students a quarter. (Medical students, medical residents and psychiatry fellows also do rotations with the unit.) But that hasn’t stopped current nurse practitioner student Kate Gieschen, RN – who recently completed a rotation with the mobile health care team – from urging her classmates to seek the experience.

“I think probably every student could benefit from rotating through and just seeing what it would be like,” says Gieschen. “This is very eye-opening for what the barriers are that many of our patients face and how you can best support them with a plan that works for them.”

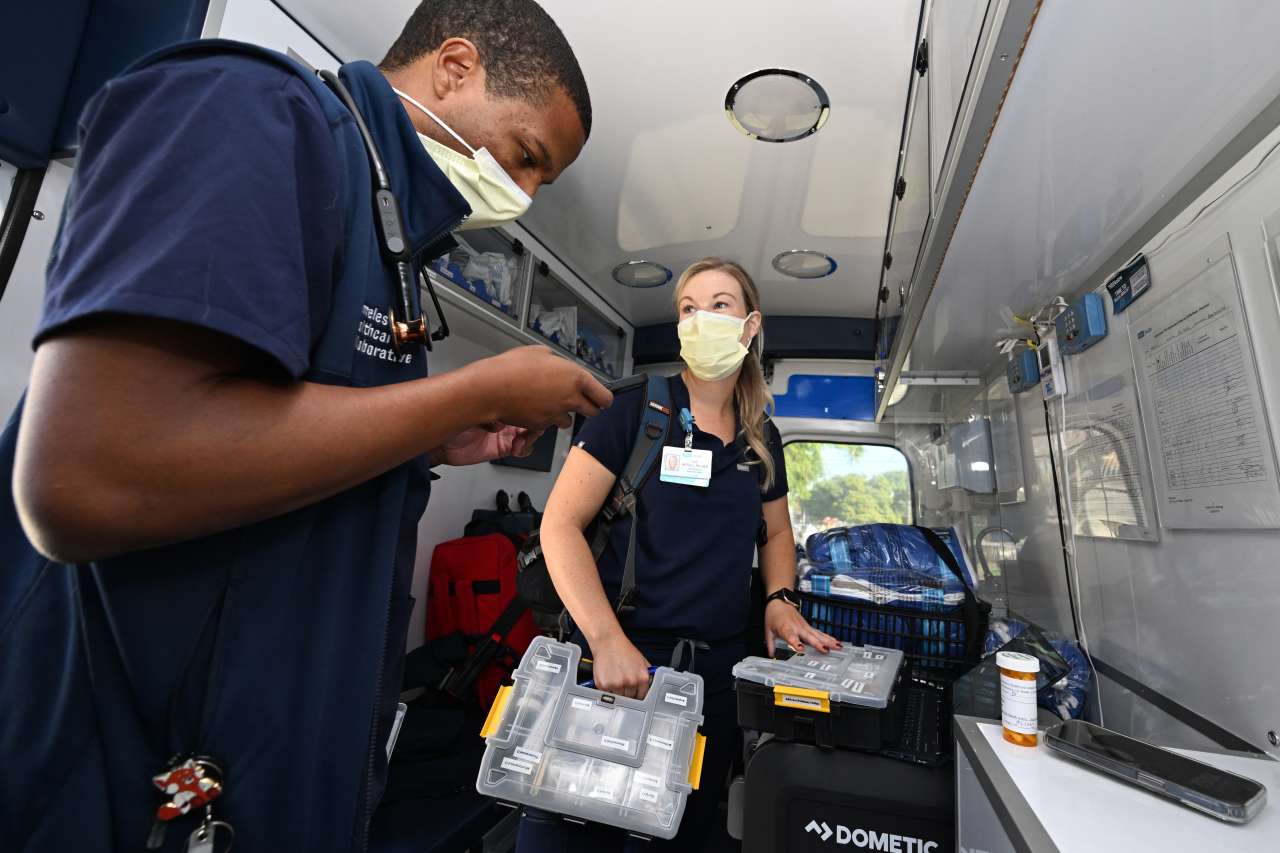

During a visit to a men’s homeless shelter in downtown Los Angeles, Gieschen worked alongside Phillip Brown, MD, an assistant clinical professor in family medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. Together, they saw at least a half-dozen patients during the van’s two-hour stop at the facility.

The men were dealing with a range of issues: some needed refills on their medications; one had muscle aches; another sought psychiatric support. Gieschen and Dr. Brown treated each like their most important patient of the day.

One patient complained of a sore throat. Gieschen gently put her hand on his back as she looked at his throat with a pen light. An observer wondered when that man had last been touched so kindly. Such physical contact can be healing on its own, Dr. Brown says: “Being empathetic can go a long way.”

Gieschen and Dr. Brown talked with each patient about any challenges that might prevent them from picking up their prescribed medications and taking them as directed. Did they need a ride to the drugstore? (If so, the mobile health van can summon a car service.) Did they have a safe place to keep their meds?

Non-compliance with medications is a common issue in health care, Gieschen says, but the challenges unhoused people face added a new dimension for her to consider.

“If your backpack’s getting stolen, how are you supposed to take your meds?” she says. “Or what meds can we give you if we don’t know that we’re going to be able to check your blood levels later?”

That kind of critical thinking and compassion for the individual and their life circumstances applies beyond caring for people who are homeless, she says: “It’s really looking at someone as an entire person – the barriers they face and the strengths they have – and making a plan for them.”

Training the next generation of providers

The Homeless Healthcare Collaborative has been a rotation site for graduate nursing students since it was established in January of 2022.

“It’s a very nontraditional type of care that we’re providing,” says Brian P. Zunner-Keating, MS, RN, director of the Homeless Healthcare Collaborative. “We’re very happy to be able to train the next generation of health leaders, really ground them in health equity, and be able to expose them early in their career to different types of care outside of a traditional hospital or clinic setting.”

In addition to working in nontraditional settings with often marginalized individuals, nursing students training with the Homeless Healthcare Collaborative are exposed to a range of patients and health conditions, Dr. Brown says.

“They get the opportunity to practice a broad scope of medicine,” he says, including pediatrics, women’s health, mental health and acute care. “With the experience they gain here, it keeps their options broad and their prospects and horizons so much more expansive.”

It’s also a powerful learning experience because of the access students have to the physicians training them, Gieschen says. Not only do they work together closely while tending to patients, but they’re literally sitting side by side in a van to and from each site.

Common humanity

Dr. Brown chose to work with the Homeless Healthcare Collaborative because he wanted to provide excellent care for people who tend to be undervalued in society. The nurse practitioner students who get to work with the mobile health unit also report experiencing an expansion of their understanding and compassion for people who might be overlooked.

“I feel like my empathy grew by leaps and bounds,” McFall says.

Working with the Homeless Healthcare Collaborative changed the direction of her career. McFall is now devoted to providing care for people affected by social determinants of health, such as lower income and education; exposure to violence, racism and unsafe neighborhoods; and reduced access to clean water, air and healthy foods.

“These are people who are caught by a safety-net health care system, and I realized that actually that’s where I want to be,” McFall says. “I want to be able to provide care to patients like this because not only do I have education and experience that I can provide in these situations, but even as a provider, it reminds me of the humanity in all of us.”