For event planner Jonathan Widener, flying was second nature. In his previous career as a flight attendant, he’d traveled to more than 50 countries, so when he boarded a client’s private plane on Aug. 13, 2012, for the short flight home from St. Louis to Chicago, he expected it to be uneventful.

But as they waited to take off, everything suddenly went black.

Widener, then 38, had suffered a grand mal seizure and gone into cardiac arrest. He was rushed to a local hospital in St. Louis, where doctors spent a week trying to determine the cause.

Given Widener’s prolific travel background, they ran numerous tests for various diseases he could have contracted in other countries. It was only after they’d ruled out other causes that they concluded Widener likely had a brain tumor, and recommended he return home to seek further care. At that point, Widener didn’t know that he indeed had a brain tumor and if so, what type it was, let alone whether it was survivable.

Since then, Widener has undergone two brain surgeries – including at UCLA Health.

Surgery to remove some of the tumor

Widener’s initial care was through Cook County Health in Chicago. The doctors there diagnosed him with an oligodendroglioma, a tumor that originates from parts of the brain itself, and prescribed anti-seizure medication along with steroids to help control the swelling in his brain.

Widener was referred by a friend to an oncological neurosurgeon at Northwestern Medicine, where he had his first surgery in early 2013. He easily recalls the date and time: The procedure took place on his birthday, Jan. 22, with the official start time coinciding with his exact time of birth.

Because of the location of Widener’s tumor within his brain, the surgeon was only safely able to remove about 60% of it. Widener underwent subsequent radiation but continued to have seizures. “They were intermittent – maybe one a week,” he said.

That became his new “normal.”

Widener continued to take various medications, including higher and higher doses of the anti-seizure drug, and had to be monitored regularly.

When he moved to San Diego in 2014, he found a new provider, David Piccioni, MD, a neuro-oncologist with UC San Diego Health. All was stable until the summer of 2018, when Dr. Piccioni informed Widener that his tumor had started to grow again. He recommended that Widener undergo a round of chemotherapy and additional radiation.

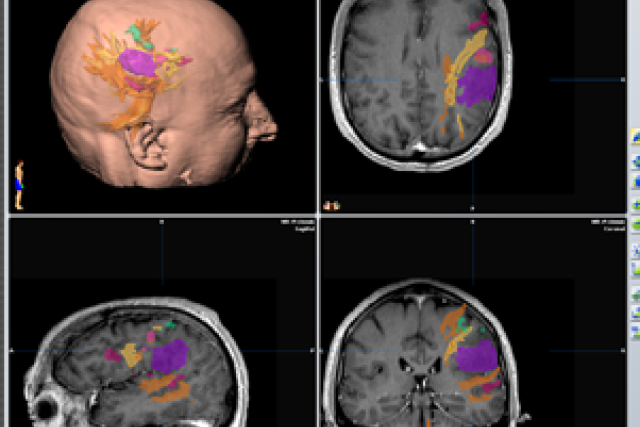

A 3D brain map to guide surgery

But for Widener, the toll of his treatments to date, coupled with his ongoing seizures, made him hesitant. Instead, he sought a second opinion and was referred to Leia Nghiemphu, MD, director of the neuro-oncology clinical service at UCLA Health and a professor of clinical neurology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

Dr. Nghiemphu recommended that Widener undergo a second surgery; from there, he was referred to neurosurgeon Linda Liau, MD, PhD, director of the UCLA Brain Tumor Program and professor of neurosurgery at the David Geffen School of Medicine.

At Widener’s first meeting with Dr. Liau, in 2018, he had a seizure in her office. “Luckily, it wasn’t a major seizure,” said Dr. Liau, a member of the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, “but it was clear that he was suffering from intractable seizures despite anti-seizure medications and needed more of his tumor taken out.”

Given the intricate nature of the surgery, however, Dr. Liau first wanted a detailed map of Widener’s brain to guide the operation.

“Sometimes tumors are close to what we call the eloquent areas of the brain – the areas that control motor, sensory, or language functions,” she explained. “Often, neurosurgeons can’t take out tumors near these areas because they don’t know exactly where these areas are relative to the tumor.”

That’s where functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which allows brain mapping before surgery, comes in. “We’re one of the leading centers that does functional MRI scanning in conjunction with intra-operative brain mapping,” Dr. Liau said. “We’re able to use cutting-edge imaging technology and brain stimulation in real time to better inform our surgeries.”

In Widener’s case, the tumor was in the frontal and parietal lobes on the left side of his brain, in between his primary motor-sensory areas and encroaching upon language areas, which made the operation more difficult.

“The left side of the brain is the side that controls language, memory and higher cognitive functions,” Dr. Liau explained.

During a pre-surgery scan, Widener was asked to perform specific tasks that then caused the corresponding areas in his brain to light up on the brain scan. That helped pinpoint which areas to avoid during surgery.

Widener’s scan was then used to create a three-dimensional model of his brain. “It takes quite a bit of post-processing to really interpret those functional MRI scans to use them for surgical localization,” Dr. Liau said.

She likened the functional mapping and planning process to being able to perform a virtual surgery ahead of time.

“It’s a very informative, interactive map – we’re able to map out not just the neurons, but also all of the fiber tracks connected to those neurons,” she said. Even so, she noted, “during surgery, we still have to stimulate the neurons in the brain to determine if they are working while we take out the tumor.”

That meant using functional mapping fused to intra-operative navigation during the surgery to precisely locate areas of the brain to stimulate and measure the response using electrodes. “For example, if I stimulate a specific area in the brain and that causes twitching in the face, arms, or legs on the opposite side, then I know that’s a primary motor area and to avoid it,” Dr. Liau said.

Although Widener’s tumor was very close to eloquent areas of the brain, Dr. Liau was able to remove most of it – “over 90% or more,” she said. Part of his tumor was in the supplementary motor areas, which meant that it was safe to remove but left him with some short-term speech and movement difficulties that improved over time.

Even so, there were some smaller parts of the tumor that were in the primary functional areas and weren’t safe to remove. “It’s always a judgment call,” Dr. Liau said. “Even with tumors where it appears that we can take it out totally, sometimes we shouldn’t, because of the long-term impact it can have on a patient’s function.”

Post-surgery

After the surgery, Widener spent about two months at California Rehabilitation Institute, a partnership between UCLA Health and Cedars-Sinai, where he re-learned basic tasks such as walking, talking and writing.

“By the time I left, I was no longer slurring words, and my physical strength had returned for the most part,” Widener said.

Widener has been seizure-free since shortly after his surgery at UCLA Health.

“That’s really one of the main reasons we do repeat surgeries,” said Dr. Liau, noting that when parts of the tumor aren’t removed the first time, patients often end up experiencing seizures or other symptoms that negatively impact their quality of life.

“We were able to take out areas of the tumor they weren’t able to get to before because of the detailed functional MRI and intra-operative mapping,” she pointed out. “At UCLA, we’re able to handle what typically would be considered inoperable tumors or tumors in inoperable areas, given the technical neurosurgical advances that we have developed here and our skilled multidisciplinary brain tumor team.”