While melanoma is relatively rare, accounting for only 1% of all skin cancer cases, rates of melanoma have been rising rapidly over the past few decades. It is responsible for the majority of skin cancer deaths, according to the American Cancer Society.

But treatments have undergone a dramatic shift, thanks to groundbreaking advancements in immunotherapy. Today, many patients who would have faced an uncertain future are living longer, healthier lives, a transformation largely driven by pioneering research led by Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD.

“When I started treating cases of melanoma that had metastasized to other organs, maybe 1 in 20 responded to treatment,” said Dr. Ribas, who directs the Tumor Immunology & Immunotherapy Program at the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. “It was the worst of the worst cancers.”

Over the last 10 years, Dr. Ribas and colleagues have made significant advancements using targeted therapies and immunotherapies that harness the body's natural defenses to fight cancer.

Improved survival rate

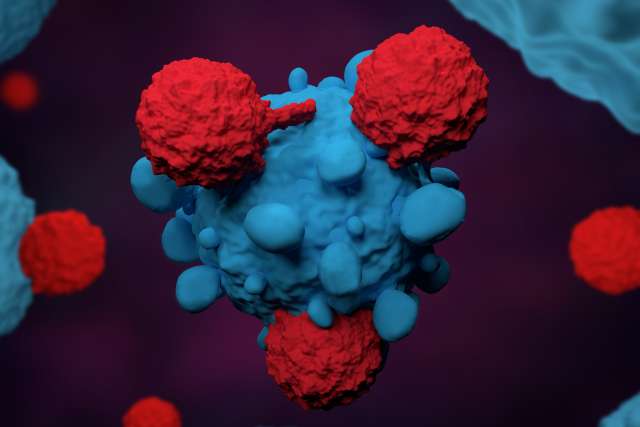

When using immunotherapy to fight cancer, the strategy for many years had been to stimulate cells of the immune system to kill the cancer cells. However, this approach had limited success, because of PD-1, a regulatory protein that hinders the immune system by preventing its T cells from recognizing and attacking cancer cells.

The turning point came in 2014, when Dr. Ribas led one of the largest phase 1 studies in the history of oncology, enrolling more than 600 patients with advanced melanoma. That study demonstrated the effectiveness of the drug pembrolizumab. By targeting PD-1, pembrolizumab (marketed under the brand name Keytruda), in effect, cuts the brake lines, freeing up the immune system to attack the cancer.

A disease once deemed untreatable now sees five-year survival rates up to 50% for many patients who respond to immunotherapy. Advanced melanoma went from being labeled as a fatal disease to one that can be cured.

But while the advancements are remarkable, immunotherapy still does not work for everyone.

“Only about half of people respond to the therapies, and that is not good enough,” said Dr. Ribas, who is also a professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and director of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at UCLA. “Our goal is to make these treatments effective for more people.”

To further improve the response rate, Dr. Ribas said, identifying mechanisms that determine how tumors can become resistant to these therapies is critical to developing improved treatments – as is understanding how to identify patients who will and will not respond to them.

Combination therapies

To enhance therapy response rates, Dr. Ribas and colleagues are conducting trials to develop new combination therapies. The latest research suggests combining checkpoint inhibitors with other agents can provide greater benefits for some patients.

Based on findings from a multicenter clinical trial co-led by Dr. Ribas, the researchers found combining two immune checkpoint inhibitors — ipilimumab and nivolumab — helped overcome resistance to prior PD-1 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma. These results prove that this combination approach should be the preferred drug regimen for people with cancer unresponsive to prior immunotherapy treatment.

Another study from the Ribas laboratory explored the use of a triple combination therapy using BRAF and MEK inhibitors along with an immune checkpoint inhibitor for the treatment of advanced melanoma. Results of the clinical trials found that people who received the combination as the initial treatment for their melanoma survived longer without the cancer progressing.

An early-stage study found an effective combination of the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab and an experimental agent with a sequence of nucleic acids that mimics a bacterial infection. This therapy altered the microenvironment around the melanoma tumor such that the immune system was more effectively able to attack the cancer. Early results showed tumor shrinkage in a subset of patients.

“Understanding the science behind how immunotherapies work in patients,” said Dr. Ribas, “allows us to explore new strategies to enhance their effectiveness.”

CAR T-cell therapies

Building on these developments, Dr. Ribas and his team are also exploring the potential of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene engineered T-cell therapy in tackling rare and hard-to-treat melanomas.

CAR T-cell therapy involves engineering a patient’s immune cells to express synthetic receptors that enable them to identify and attack tumor cells based on specific surface proteins.

Alongside researchers at Stanford and City of Hope, Dr. Ribas is investigating the use of CAR T-cell therapy to treat patients whose tumors express a protein called IL13Ra2. This protein target is commonly found among patients with melanoma, as well as some thyroid cancers, neuroendocrine tumors, adrenocortical carcinoma, paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma. The team was recently awarded a $10.2 million grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) to help fund the team’s phase I clinical trial.

Another development, in collaboration with Cristina Puig-Saus, PhD, an assistant professor of microbiology, immunology, and molecular genetics and surgical oncology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, includes using CAR T cells to treat rare forms of melanoma including acral, uveal and mucosal melanoma. The new approach is designed to recognize and attack cells with high levels of TYRP1, a protein found on the surface of melanoma cells.

To investigate the potential new target, the team designed a CAR construct that specifically targeted cells with elevated TYRP1 expression. In preclinical tests, the team found these engineered CAR T cells can effectively eliminate cancer cells without causing severe side effects. Thanks to a $5.9 million award from CIRM, the research team is now planning to move forward with a clinical trial to assess the therapy's safety and effectiveness.

This progress is part of Dr. Ribas’ broader vision to offer even more targeted and effective treatments for patients with melanoma and other difficult-to-treat cancers. His mission is clear: to continually refine therapies, reduce side effects and expand treatment options for all who need them.

“The last decade has been transformative, but we’re just getting started,” he said.